- www.medievalists.net Medieval and Viking-Age artifacts discovered in Norway - Medievalists.net

A very rare Byzantine coin is among dozens of medieval and Viking-era objects discovered in eastern Norway last year. Officials with Innlandet County Municipality have released details of items found by metal detectorists, including buckles, seals and pieces from swords.

- www.sciencenorway.no Norwegian archaeology find of the year: A 4,000-year-old grave with skeletons

The grave is approximately as old as the pyramids and contained remains of at least five people.

- phys.org Understanding the role of pareidolia in early human cave art

A psychological phenomenon where people see meaningful forms in random patterns, such as seeing faces in clouds, may have stimulated early humans to make cave art.

A psychological phenomenon where people see meaningful forms in random patterns, such as seeing faces in clouds, may have stimulated early humans to make cave art.

- phys.org New Indo-European language discovered during excavation in Turkey

An excavation in Turkey has brought to light an unknown Indo-European language. Professor Daniel Schwemer, an expert for the ancient Near East, is involved in investigating the discovery.

An excavation in Turkey has brought to light an unknown Indo-European language. Professor Daniel Schwemer, an expert for the ancient Near East, is involved in investigating the discovery.

-

Chemical Analysis of Viking Combs Hints at Long-Distance Trade

YORK, ENGLAND—According to a statement released by the University of York, a new analysis of collagen extracted from Viking hair combs by researchers from the University of York, University of Stockholm, the University of Barcelona, the Center for Baltic and Scandinavian Archaeology, and the Leibniz Center for Archaeology suggests trade between the Viking settlement of Hedeby in Germany and northern Scandinavia may have originated earlier than previously thought. Large amounts of craft production waste, mostly comprised of red deer antler, has been recovered at Hedeby, a major antler-working center. But the study found that 85 to 90 percent of the finished antler combs unearthed in Hedeby had been made from the antlers of reindeer, which live in northern Scandinavia. The study therefore indicates that the combs unearthed at Hedeby had been manufactured elsewhere and then transported on a large scale as early as A.D. 800. Read the original scholarly article about this research in Antiquity.

-

Hominins Built Wooden Structures and Transformed Environment

LIVERPOOL, ENGLAND—The Guardian reports that remains of a wooden structure built by hominins has been discovered near Zambia’s Kalambo Falls by a team of researchers led by Larry Barham of the University of Liverpool. The materials have been dated to least 476,000 years ago by team members from the University of Aberystwyth with luminescence dating techniques, which reveal the last time minerals in the sands surrounding the artifacts had been exposed to sunlight. The remains of the structure include two logs bearing cutting, chopping, and scraping marks made with stone tools also found at the site. The end of one log crosses the second and is held in place with a large notch. “When I first saw it, I thought this can’t be real,” Barham said. He thinks the structure may have been part of a walkway or a foundation for a platform. “A platform could be used as a place to store things, to keep firewood or food dry, or it might have been a place to sit and make things. You could put a little shelter on top and sleep there,” he explained. The dating of the structure indicates it could have been made by Homo heidelbergensis, a hominin that lived in the region at the time. During their investigation of the Kalambo Falls area, Barham and his colleagues also recovered a wooden wedge, a split branch with a notch in it that may have been part of a trap, and a log that had been cut at both ends.

-

Scientists discover evidence of extinct species of humans from half a million years ago

www.independent.co.uk Scientists discover evidence of extinct species of humansThe discovery is likely to change archaeologists’ understanding of the evolution of early human technology

-

Civil War Remains Identified in Williamsburg

WILLIAMSBURG, VIRGINIA—Colonial Williamsburg archaeologists have determined that the remains of 21 or 22 men found in a historic area of the city belong to Confederate soldiers, according to a report in the Daily Press. The men likely died in a Union-operated hospital established after the Battle of Williamsburg on May 5, 1862, which claimed the lives of 1,682 Confederate soldiers and 2,283 Union soldiers. The men’s remains will eventually be reburied, along with the artifacts found with them, including a snuff bottle, toothbrush, buttons, and gold coins. “I’m really happy we’re able to work toward identifying these guys (and) then provide some level to dignity” in their reburial, said Jack Gary, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s director of archaeology who is leading the recovery project.

-

Grieving Wordsworth found solace in poignant shipwreck treasure after brother’s death

When the Romantic poet’s younger brother John died at sea, marine artefacts helped him bear the loss, research reveals

When William Wordsworth’s beloved younger brother John died on a ship that sank in rough seas off the coast of Dorset in 1805, the great Romantic poet dealt with his sorrow by writing of the “calamitous” loss: “Sea, Ship, drown’d, Shipwreck – so it came/The meek, the brave, the good, was gone;/ He who had been our living John/ Was nothing but a name.”

John was captain of the East India Company’s largest ship, the Earl of Abergavenny, which sank after hitting rocks shortly after embarking on a trading voyage to China. He was among more than 250 crew and passengers who perished on a bitterly cold February night.

- www.theguardian.com Revival of Stonehenge road tunnel plan triggers new legal challenge

Campaigners to return to the courts after planned two-mile tunnel near site, blocked in 2021, is greenlit again

Campaigners to return to the courts after planned two-mile tunnel near site, blocked in 2021, is greenlit again

Campaigners have launched a fresh legal battle after the government once again greenlit plans for a controversial road tunnel at Stonehenge, after the development was successfully blocked two years ago.

The Save Stonehenge World Heritage Site campaign (SSWHS) is challenging the decision by the transport secretary, Mark Harper, to allow a £1.7bn scheme to widen roads and dig a two-mile tunnel near the ancient site. The plan is designed to improve traffic on the A303, a congestion hotspot in south-west England.

- www.theguardian.com ‘Nobody was expecting it’: British Museum warned reputation seriously damaged and treasures will take decades to recover

Experts say loss of 1,500 items reveals lax cataloguing and boosts case for returning objects to countries of origin

Experts say loss of 1,500 items reveals lax cataloguing and boosts case for returning objects to countries of origin

Close observers of the antiquities market tend to be a cynical bunch, having witnessed any number of scams, dubious practices and illicit trading. Yet there was a collective expression of shock among them last week when news emerged of the unexplained absence of a reported around 2,000 items from the British Museum’s priceless collection of ancient and historical artefacts, leading to the resignation of director Hartwig Fischer.

“The volume of missing objects is huge,” says Christos Tsirogiannis, a forensic archaeologist who works with Trafficking Culture, which researches global traffic in looted cultural objects. “No experts were expecting this to happen in one of the world’s biggest museums.”

- phys.org Doctoral thesis: The land use of West Estonian lowlands in Late Stone Age turned out to be seasonal

At the end of the Middle Stone Age and during the Late Stone Age, settlements in the West Estonian lowlands were more seasonal than in the neighboring areas of the island of Saaremaa and the Pärnu Bay catchment area, indicates the study conducted by Kristjan Sander who defended his doctoral thesis a...

At the end of the Middle Stone Age and during the Late Stone Age, settlements in the West Estonian lowlands were more seasonal than in the neighboring areas of the island of Saaremaa and the Pärnu Bay catchment area, indicates the study conducted by Kristjan Sander who defended his doctoral thesis at Tallinn University's School of Humanities. The doctoral thesis examines the period of approximately 5300-2600 BC.

The time frame of the thesis begins with the end of the maximum water level of one of the development stages of the Baltic Sea following the Last Glacial Period—the Littorina Sea—since which the sea level in Estonia has been continuously falling. To this day, post-glacial rebound is particularly fast in West and North-West Estonia, and the ancient coastlines are now located as far as up to 30 km inland in certain locations. In many places, millennia-old beach formations are still visible in nature today.

In the two geographical areas examined, Kristjan Sander searched for settlements of Stone Age people on the land freed from under the sea as a result of post-glacial rebound and on inland riverbanks up to 10 km from the coastline of the Littorina Sea at its maximum water level.

One of the areas studied is situated in North-West Estonia, embracing the peninsulas bordering the sea bay that lay there in the place of the present-day Suursoo, and, further northwest, the Elbiku mountain that was once an island located up to 15 km from the coast.

Fieldwork took place in the villages of Kõmmaste, Risti, Vilivalla, Vihterpalu, Variku, and Nõmmemaa. The second examined area is situated on the beach of Ancient Matsalu Bay on the Üdruma—Teenuse—Vana-Vigala—Avaste route and on the southern edge of Matsalu National Park where the current highlands (Kirbla, Lautna, Kloostri, Hälvati, Lihula, Massu, and Salevere) formed an archipelago resembling today's Väinameri Sea.

New settlements were searched for by collecting finds on open land, i.e. plowed fields, allotments, road verges, firebreaks, forest roads, and clearings.

Kristjan Sander's doctoral thesis fills a big gap in studying Stone Age in Estonia as prior to Sander's exploration only four settlements and one burial site were known in Western Estonian lowlands. During fieldwork, 102 settlements (at least 3 finds) and 39 incidental discovery sites were mapped.

Surprisingly, no settlements were identified that could, based on the material found and dimensions established, be considered more permanent in nature as are known settlements in the neighboring Pärnu Bay catchment area and the island of Saaremaa. Regarding the studied period, solely seasonal land use in large areas like the ones in question is a new discovery on the entire eastern shore of the Baltic Sea, although individual seasonal settlements have also been described earlier.

Stone Age settlements in Western Estonia expanded on different terrains at different times. The oldest settlements of the Middle Stone Age are located at river estuaries and ancient coastal lagoons as well as at the tips of peninsulas. At the end of the Middle Stone Age at the latest, starting from the Narva stage (5200-3900 BC), small islands were also made use of. At the beginning of the New Stone Age, in the Comb Ware stage (approx. 3900–1800 BC), additional settlements were built on the riverbanks near the coast.

Based on ethnographic analogies, Sander hypothesizes that the observed settlement dynamics are caused by the intensification of fishing in response to the slow cooling of the climate. It can be assumed then that the seasonal settlement situated in the southern area examined originated from Saaremaa island as inhabitants of the Pärnu Bay catchment area already had an abundance of large rivers rich in fish.

Assembling such a broader picture of settlements provides an insight into the ways of life and society of the distant past that cannot be replaced by excavation of individual settlements. However, archaeological excavations are indeed required to investigate the activities that took place in the newly identified settlements.

-

Possible Evidence of Deer Sacrifice Uncovered in England

Skeletons of two red deer dating to the Bronze Age were unearthed in an ancient pit during work to build a new water grid across the East of England, according to a statement released by Anglian Water. The deer bones, which were buried more than 4,000 years ago, bear no signs of butchery. Alongside the remains, archaeologists found pottery made by members of the Bell Beaker culture, who originated in Europe and began to produce their distinctive, bell-shaped ceramics between 2800 and 2300 B.C. "The red deer may have been left as a sacrifice or offering by Early Bronze Age people," project archaeologist Jonathan Hutchings said. "Alternatively, it could have been a sort of ‘funeral’ for the deer, or a way to ward off or attract spirits."

- phys.org The idea that imprisonment 'corrects' prisoners stretches back to some of the earliest texts in history

Prisons are places of suffering. But in theory, they aim for something beyond punishment: reform.

Prisons are places of suffering. But in theory, they aim for something beyond punishment: reform.

In the United States, the goal of prisoner rehabilitation can be traced back, in part, to the 1876 opening of the Elmira Reformatory in upstate New York. Purported to be an institution of "benevolent reform," the reformatory aimed to transform prisoners, not just deprive them—though founder Zebulon Brockway, known as the "Father of American Corrections," was notoriously harsh.

Other states soon adopted the reformatory model, and the notion that prisons are places to "correct" people has become a staple of the judicial system.

But the idea that imprisonment and suffering were supposedly good for the prisoner didn't emerge in the 19th century. The earliest evidence goes back some 4,000 years: to a hymn in Mesopotamia, in modern-day Iraq, praising a prison goddess named Nungal.

Almost a decade ago, as a graduate student researching slavery in early Mesopotamia, I came across numerous texts dealing with imprisonment. Some were administrative documents dealing with everyday accounting information. Others were legal texts, literature or personal letters. I became fascinated with imprisonment in these cultures: Most of them detained suspects only briefly, but in literary and ritual texts, imprisonment was seen as a transformative, purifying experience.

- phys.org Study finds evidence of the formation and structural evolution of prehistoric agricultural economy in Central China

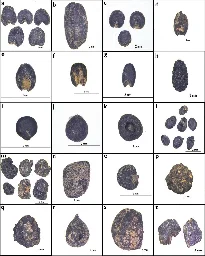

A research team led by Prof. Yang Yuzhang from the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) investigated the human subsistence strategy evolution of agricultural structure during the Yangshao culture period (ca. 6400-5300 cal. BP) at Changge Shigu...

A research team led by Prof. Yang Yuzhang from the University of Science and Technology of China (USTC) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) investigated the human subsistence strategy evolution of agricultural structure during the Yangshao culture period (ca. 6400-5300 cal. BP) at Changge Shigu, a representative prehistoric site in the Central Plains region.

The study was published in Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences.

Previous studies have shown that in the middle and late Yangshao culture (ca. 6000-5000 BP), all major regional civilizations in China established agricultural production as the mainstay of the ancestors' living economy.

The Central Plains region, with west-central Henan and south-central Shanxi as its core, played a leading role in the origin and early development of Chinese civilization, which is closely related to the sustained development of the agricultural economy and the formation of a diversified crop cultivation system in the region 6,000 years before present.

However, due to a lack of reliable archaeobotanical evidence and accurate chronological data, the archaeological community is still unclear about the exact time and structural evolution of the Yangshao-era agricultural economy in the region.

In this study, the researchers employed the method of analyzing the charred plant remains, combined with the high-precision accelerator mass spectrometer (AMS) 14C dating of a series of samples.

The results showed that the identifiable charred plant remains found in the flotation soil samples of the Yangshao culture period at the Shigu site are dominated by three kinds of crops planted, namely broomcorn millet, foxtail millet, and rice, as well as various kinds of field weed seeds, among which the crops occupied a dominant position. the proportion of rice is lower than those of millet. Weed seeds are predominantly from the grass family.

The results also showed that agricultural production based on the cultivation of two types of millets, namely the dryland crops, has become the main way of obtaining plant food resources for the ancestors of Shigu, and the main position of the agricultural economy in the Central Plains region has been established 6,400 years ago.

Since the Yangshao culture 6,000 years ago, the proportion of rice in the site significantly declined. The millets took an absolute main position in the agricultural structure. This change is attributed to the deterioration of the climate environment at that time.

This study clarifies for the first time the exact time of the formation of the prehistoric agricultural economy in the Central Plains, the core area of the origin of Chinese civilization, as well as the evolution process of the economic structure of rice and millet farming and its possible driving factors in the Yangshao culture period (ca. 7000-5000 BP) in the study area. The results provide key research materials for the evolution of prehistoric human subsistence strategy, agricultural economy, and the origin of civilization in the Central Plains region.

-

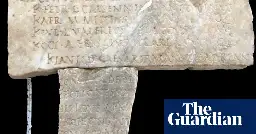

Roman Calendar Fragments Found at Ostia

According to a report in The Guardian, archaeologists working at the site of Ostia Antica about 20 miles from Rome have uncovered fragments of marble slabs called fasti recording official events that took place in A.D. 128 during the reign of the emperor Hadrian (reigned A.D. 117–138). One of the dates mentioned is January 10th, when the emperor was given the title of pater patriae, or father of the country, and his wife, Sabina, received the title Augusta. Hadrian’s April 11th trip to Africa is also noted, as is his dedication of a building in Rome which may be the Pantheon. Alessandro D’Alessio, director of the Ostia Antica Archaeological Park, calls the discovery “extraordinary” and believes that it will reveal more about the activities of the famous emperor and about ancient Ostia as well.

-

2,000-Year-Old Roman Walls Discovered in Swiss Alps

According to a SWI report, researchers have discovered the remnants of Roman walls in the foothills of the Alps while excavating a gravel pit in present-day Cham, a municipality in central Switzerland's canton Zug. Constructed some 2,000 years ago, the walls once surrounded a series of Roman buildings. The excavation also unearthed fragments from a plaster wall; iron nails; gold fragments of what may have been jewelry; and everyday items including bowls, millstones, glassware, crockery, and amphoras. The rare find, which the Office for the Preservation of Monuments and Archaeology called “sensational,” is the first in the area for nearly a century. The purpose of the building complex, which likely spanned more than 5,000 square feet, remains unknown. Further research will aim to ascertain its role in Roman society, whether a villa, an inn, a temple, or another type of building.

-

Sequencing genes of Iron and Bronze Age peoples to better understand early Mediterranean migration patterns

An international team of anthropologists, archaeologists and geneticists has learned more about the migration patterns of people living around the Mediterranean Sea during the Iron and Bronze ages. In their study, reported in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution, the group conducted genetic sequencing on the remains of 30 people who lived during the Iron or Bronze Age in Italy, Tunisia and Sardinia.

-

Ancient metal cauldrons give us clues about what people ate in the Bronze Age

Archaeologists have long been drawing conclusions about how ancient tools were used by the people who crafted them based on written records and context clues. But with dietary practices, they have had to make assumptions about what was eaten and how it was prepared.

-

Atlatl weapon use by prehistoric females equalized the division of labor while hunting, experimental study shows

A new study led by archaeologist Michelle Bebber, Ph.D., an assistant professor in Kent State University's Department of Anthropology, has demonstrated that the atlatl (i.e., spear thrower) functions as an "equalizer," a finding which supports women's potential active role as prehistoric hunters.

-

Early Island Sugar Plantation Site Investigated

COLOGNE, GERMANY—According to a Live Science report, M. Dores Cruz of the University of Cologne and her colleagues have found early evidence for the practice of plantation slavery at Praia Melão, the recently identified site of a sixteenth-century sugar mill on the northeastern coast of the island of São Tomé. The Portuguese inhabited the island, which is located off the coast of West Africa in the Gulf of Guinea, in the late fifteenth century. They soon found, however, that migrants to the previously uninhabited island endured high rates of malaria. Convicts, Jewish children, and enslaved Africans were soon forced to work there, harvesting and processing sugar cane, and building and maintaining the sugar mills. Praia Melão includes a large stone two-story building with a clay roof. Its lower floor served as a sugar boiling room, while domestic quarters were placed on the upper floor. Fragments of cone-shaped sugar molds similar to those found at Portuguese sugar mills in Madeira have also been recovered at the site. By 1530, plantations on São Tomé were so profitable that additional sugar mills were constructed, but the Portuguese eventually moved much of their sugar production to Brazil in the early seventeenth century. Read the original scholarly article about this research in Antiquity.

-

Human Remains and Jade Ring Found at Maya Site in Mexico

CAMPECHE, MEXICO—According to a statement released by Mexico’s National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), a 1,200-year-old ritual deposit has been found in a platform at a monumental complex at the Maya site of El Tigre in southeastern Mexico. The deposit contained two ceramic vessels with lids, whose style suggests that they date to sometime between A.D. 600 and 800. One of the vessels contained the skeletal remains of a young person in a flexed position and a well-preserved jade ring. INAH general director Diego Prieto Hernández said that the remains will be carefully excavated from the vessel in the laboratory, noting that the soil would be searched for any other artifacts and analyzed for any traces of pollen or seeds.

-

Museums and Artifacts Are Likely Lost in Maui Wildfires

LAHAINA, MAUI—Time Magazine reports that Kimberly Flook of the Lahaina Restoration Foundation and her colleagues estimate that at least four museums and thousands of artifacts have been lost in the recent wildfires. Among the objects believed to be lost is an original flag of the Hawaiian kingdom, last flown on August 12, 1898, when it was replaced with the American flag. Hawaiian feather work, furniture, photographs, and objects made of kapa, a fabric made of fibers from trees and shrubs, are also likely to be gone. The destroyed or damaged museums include the Wo Hing Museum & Cookhouse, a social hall for Chinese immigrants who built tunnels and irrigations systems; the Baldwin Home, which was the oldest standing residence on the island; and the Old Lahaina prison, which dates to the whaling era of the mid-nineteenth century. “We’ve lost physical pieces of history,” Flook said. “We have not lost our history, our culture. And we won’t."

- www.theguardian.com Bedroom ‘used by slaves’ found by archaeologists near Pompeii

Finding at Civita Giuliana villa throws light on lowly status of slaves in ancient world

Finding at Civita Giuliana villa throws light on lowly status of slaves in ancient world

Archaeologists have discovered a small bedroom in a Roman villa near Pompeii that was almost certainly used by slaves, throwing light on their lowly status in the ancient world, Italy’s culture ministry said on Sunday.

The room was found at the Civita Giuliana villa, some 600 metres (2,000ft) north of the walls of Pompeii, which was wiped out by a volcanic eruption of Mount Vesuvius nearly 2,000 years ago.

- www.biblicalarchaeology.org Canaan’s Earliest City Gate

What ancient site features the earliest city gate? In Israel, at least, that would be the Early Bronze Age site of Tel Erani. During a salvage excavation

What ancient site features the earliest city gate? In Israel, at least, that would be the Early Bronze Age site of Tel Erani. During a salvage excavation of the site by the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA), archaeologists discovered the impressive stone gateway built into the city’s mudbrick fortification wall. Dating to around 3300 BCE, Tel Erani’s city gate is now the oldest ever found in Israel, making it several hundred years older than the gate from Tel Arad, another Early Bronze Age city. But why did Erani’s residents need the gate in the first place?

-

Strange burial of 9th-century teenager reveals tragic story

archaeology-in-europe.blogspot.com Archaeology in Europe NewsArchaeological news from the Archaeology in Europe web site

English archaeologists have announced the discovery of the remains of a teenage girl buried in the Early Middle Ages. The circumstances of her burial were very unusual, suggesting she may have led a tragic life.

In ninth-century Cambridgeshire, as a community prepared to abandon their settlement, they took down the elaborate entrance gate and replaced it with a grave. In it were the remains of a young woman, aged just 15, buried face down in a pit and perhaps with her ankles bound together. This unusual grave gives us insight into a rare Early Medieval burial practice, and perhaps even contemporary attitudes towards those within the community who were considered different.

- www.theguardian.com Roman fragments offer glimpse of emperor Hadrian’s daily events calendar

Researchers in Italy uncover inscribed sections of marble chronicle linked to previous finds at Ostia Antica archaeological park

Some of the daily activities of the Roman emperor Hadrian, who built monuments including the Pantheon during his more than two-decade reign, have been revealed after the discovery of fragments of marble slabs in Ostia Antica, an archaeological park close to Rome that was once the city’s harbour.

The details were inscribed on fasti ostienses, a type of calendar chronicling events involving emperors and other officials in ancient Rome which were drafted by the pontifex Volcani, the highest local religious authority.

One of the two newly recovered fragments, which experts say matches perfectly with another previously found at the site, dates to AD128, during the reign of Hadrian. The inscription refers to events that took place that year, including 10 January, when Hadrian received the title pater patriae, or father of his country, and his wife, Sabina, that of Augusta. According to the inscription, Hadrian celebrated the occasion by offering a congiar dedit, or donation of money, to the people.

Another date, 11 April of the same year, refers to Hadrian’s trip to Africa before he returned to Rome between July and August. Before a subsequent trip to Athens, he consecrated (the inscription reads “consecravit”) a building in Rome that experts believe could be either the Pantheon or the Temple of Venus and Roma, possibly on 11 August. This would have marked his 11th anniversary as emperor.

The fragments were found in the forum of Porta Marina, a large rectangular building where fasti ostienses were carved into columns, during recent excavations at Ostia Antica that involved teams of archaeologists from the University of Catania and Polytechnic University of Bari.

Alessandro D’Alessio, the director of the archaeological park, said the “extraordinary discovery” sheds more light on the activities of Hadrian, including the buildings he constructed in Rome, while helping to better understand the story of ancient Ostia.

Gennaro Sangiuliano, Italy’s culture minister, said the excavations, which have also revealed extensive sections of a mosaic floor that will eventually be open to the public, gave additional insight into life in Ostia and Rome.

Fragments of fasti ostienses were first discovered at the site in 1940 and 1941 and then again between 1969 and 1972, including one that joins the recently rediscovered fragment. The combined slab chronicles the AD126-128 period. Some of the calendar fragments, which range between AD49 and AD175, are on display at the Vatican Museums.

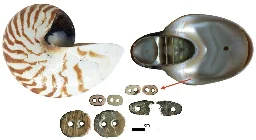

- phys.org Sea sequin 'bling' links Indonesian islands' ancient communities

A team of researchers have found a shared penchant for sewing reflective shell beads onto clothing and other items across three Indonesian islands that dates back to at least 12,000 years ago.

A team of researchers have found a shared penchant for sewing reflective shell beads onto clothing and other items across three Indonesian islands that dates back to at least 12,000 years ago.

The team, led by the Australian National University's Professor Sue O'Connor with Griffith University's Associate Professor Michelle Langley, used advanced microscopic analysis to investigate Nautilus shell beads from Makpan Cave on the Indonesian island of Alor, and that the trends in style were shared with at least two other islands.

Striking similarities between the beads of Alor, Timor, and Kisar indicate that there was a shared affinity for sewing the reflective beads onto clothing or other items, therefore, the team deduced that there must have been shared ornament traditions across the sea in the region from the Terminal Pleistocene (late Ice Age) around 12,000 years ago.

Recent DNA evidence has shown how people on different Indonesian islands were genetically related, but until now it wasn't known how culturally similar the populations were.

To answer this question, the Griffith and ANU teams analyzed the beads from Makpan and found that not only were they incredibly consistent in their method of production, but also similar to beads previously found on the islands of Timor and Kisar.

"The time and skill required to create the tiny shiny beads in the numbers found archaeologically must have been extensive, suggesting that the beads were an important part of the Makpan community's repertoire of adornment," said Associate Professor Langley, lead author of the article published in Antiquity. It is titled "Sequins from the sea: Nautilus shell bead technology at Makpan, Alor Island, Indonesia."

There was also an intensification in fishing technology during this period with shell fishhooks appearing at associated sites, as well as exotic obsidian and artifacts appearing in the assemblages.

The similarity between the beads and fishhooks from different islands coupled with the skill and effort required to produce them implies that the practice was a tradition shared between islands, indicating frequent interaction across the sea.

Furthermore, the team who excavated at Makpan found thousands of shells in the food waste.

"What is interesting," said ANU's Dr. Shimona Kealy, "is that Nautilus shells, which were used to make the beads, are almost entirely absent from this discard pile of ancient shellfish feasts, indicating that Nautilus was not collected for food but specifically for crafting."

Professor Sue O'Connor recalls, "When we were excavating at Makpan Cave in Alor we were amazed at how many shell beads we were finding, and how we just kept on finding them even into the lowest levels of the excavation. In view of the great depth of the excavation we thought that there was a high likelihood that the oldest beads would be in Pleistocene-aged deposits."

Importantly, this means that Makpan's occupants were collecting Nautilus purely for the purpose of making beads. This presents a society that was secure enough to invest effort into harvesting and processing resources for aesthetic uses without any obvious practical benefit.

All of these factors combine to create "an image of an inter-island 'community of practice' with shared values and worldviews" said Associate Professor Langley.

"It is likely that the populations of these islands shared a distinctive culture, exchanging style, goods, technology and genes across the sea."

- phys.org Exploring South Australia's oldest shipwreck

The Australian National Maritime Museum (ANMM) and non-profit Silentworld Foundation have continued ongoing archaeological investigation of the wreck of South Australian, with recent research from a combined team of experts published in the journal Historical Archaeology.

The Australian National Maritime Museum (ANMM) and non-profit Silentworld Foundation have continued ongoing archaeological investigation of the wreck of South Australian, with recent research from a combined team of experts published in the journal Historical Archaeology.

The South Australian is South Australia's oldest known European shipwreck. The English barque, wrecked in in 1837 in Encounter Bay near modern-day Victor Harbor, has drawn keen interest since its discovery in 2018. The wreck site project team includes members of the ANMM, Silentworld Foundation, South Australian Maritime Museum, South Australia's Department for Environment and Water, Flinders University, and MaP fund.

Originally a postal packet called Marquess of Salisbury, which delivered mail between England and far-flung outposts of the British Empire from 1820, the vessel later operated as a British naval packet, named HMP Swallow, before being procured by the South Australian Company, which re-named the ship South Australian.

The ship was designed to carry a huge amount of sail on a relatively small hull for maximum speed. While it transported approximately 80 immigrants to the new colony, its primary function was as a "cutting-in" vessel, or flensing platform, where blubber was removed from harpooned whales as part of the shore-based whaling industry at Encounter Bay.

While loaded with whale oil and readying for departure to Hobart, South Australian was caught in a south easterly gale and wrecked on 8 December 1837. There were no fatalities, and the ship ultimately broke up and was forgotten until the 1990s, when it was the subject of two unsuccessful shipwreck surveys conducted by the South Australian government.

Data collected during these expeditions and archival information helped the research team to establish a new search area that led to South Australian's discovery in April 2018. Remnants of the ship exposed above the seabed included timber framing and hull planking, copper keel bolts, and fragments of glass and pottery.

COVID-19 travel restrictions interrupted further visits to South Australian for two years, but in 2022 maritime archaeologists from the ANMM and an archaeological conservator from the Silentworld Foundation, accompanied by volunteers, returned to continue work at the site.

Photogrammetric 3D recording was carried out in conjunction with site mapping. The team also conducted a comprehensive conservation assessment to determine the wreck site's level of preservation and suggest strategies for its continued protection.

Ongoing work at the site has included comprehensive documentation of exposed hull components and targeted recovery of at-risk diagnostic artifacts. A small selection of objects was also mapped in place and recovered. The items include a gun flint, decorated ceramic fragments, ship's fasteners, glass bottles and a whetstone used to sharpen tools. All are currently undergoing conservation.

Dr. James Hunter, ANMM's Curator of Naval Heritage and Archaeology, and an Associate Lecturer of Archaeology at Flinders University, concluded in the article recently published in Historical Archaeology:

"South Australian's historical and archaeological significance cannot be overstated. As South Australia's oldest recorded European shipwreck, and one of its earliest immigration vessels, it has the potential to enhance our understanding of the state's initial colonization and occupation—including the establishment of extractive mercantile activities, such as shore-based whaling and interactions between European colonists and Aboriginal people.

"Similarly, the site's distinction as one of only two (former) 19th-century British sailing-packet shipwrecks to undergo archaeological scrutiny brings an international dimension to its significance. While a sizable percentage of South Australian's surviving fabric remains buried, recent seabed changes are uncovering the site at an alarming rate. This has reinforced the need for additional investigation and inquiry and underscores the urgency with which site stabilization efforts should be adopted and enacted."

While weather and water visibility impeded efforts to complete the 3D photogrammetric survey of South Australian in late 2022, imagery from this and prior surveys has since been used to generate a digital 3D model of most of the site. This in turn will form the basis of a virtual reality experience currently under development at Germany's University of Applied Sciences, Kaiserslautern. South Australian is also the subject of a graphic novel based on research and archival sources, including the original logbook, which will bring its story to vivid life for new audiences.

The team's work continues, and they aim to conduct further archaeological investigation of South Australian and finish the photogrammetric survey during the latter half of 2023.

-

Votive Cache Unearthed in Sicily’s Valley of the Temples

AGRIGENTUM, SICILY—According to a statement released by the Sicilian Region Institutional Portal, an excavation led by archaeologist Maria Concetta Parello at House VII b in Sicily’s Valley of the Temples has uncovered a votive deposit containing at least 60 terracotta figurines, oil lamps, small vases, bronze fragments, and bones. The deposit was found above a destruction layer attributed to the burning of the Greek city in 406 B.C. by the Carthaginians. Parello and her colleagues will try to determine if the objects were left by residents who returned to their ruined city.

-

Bronze Age Pyramid Discovered in Kazakhstan

TOKTAMYS, KAZAKHSTAN—The Miami Herald reports that a 4,000-year-old stone structure has been unearthed in northern Kazakhstan’s Kyrykungir monumental complex. “The steppe pyramid is built with great precision,” said Ulan Umitkaliyev of Eurasian National University. “It is a very sophisticated complex structure with several circles in the middle.” A large black stone with a flattened side sits at the end of each exterior wall, he added, while the walls are decorated with images of horses and other animals. Horse bones have also been found nearby, suggesting that the building may have been linked to a horse cult, Umitkaliyev explained. Pottery, gold earrings, and other jewelry have also been uncovered at the site.

-

New Thoughts on Cattle in the American Colonies

GAINESVILLE, FLORIDA—According to a statement released by the Florida Museum of Natural History, analysis of DNA samples taken from cattle remains unearthed in Spanish settlements in the Caribbean and Mexico indicates that cattle may have been imported from Africa in the early seventeenth century, some 100 years earlier than previously thought. Research team leader Nicolas Delsol said that the Spanish transported cattle from Europe in the early sixteenth century, and, indeed, the DNA analysis determined that cattle in Puerto Real, Hispaniola, are closely related to modern European cattle. Six of the cattle bones unearthed in Mexico carried DNA sequences that are common in African cattle, but are also found in modern European breeds. “There are cattle in Spain similar to those in Africa due to centuries-long exchanges across the Strait of Gibraltar,” Delsol explained. But a sample of mitochondrial DNA from a late seventeenth-century cattle tooth found in Mexico contained a genetic signature rarely found outside of Africa. Delsol and his colleagues think this animal may have descended from cattle that were transported from West Africa directly to the Americas with enslaved peoples. Read the original scholarly article about this research in Scientific Reports.

- phys.org Archaeologists uncover Europe's oldest stilt village

Beneath the turquoise waters of Lake Ohrid, the "Pearl of the Balkans", scientists have uncovered what may be one of Europe's earliest sedentary communities, and are trying to solve the mystery of why it sheltered behind a fortress of defensive spikes.

Beneath the turquoise waters of Lake Ohrid, the "Pearl of the Balkans", scientists have uncovered what may be one of Europe's earliest sedentary communities, and are trying to solve the mystery of why it sheltered behind a fortress of defensive spikes.

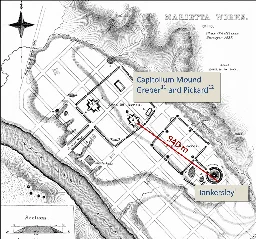

- phys.org Archaeologists refute claims that a comet destroyed Hopewell culture

In February 2022, the journal Scientific Reports published a paper with the claim that a comet exploded over what is now Cincinnati around 1,500 years ago, raining fire over the area and destroying villages and farm fields, supposedly resulting in the rapid decline of the ancient Indigenous Hopewell...

In February 2022, the journal Scientific Reports published a paper with the claim that a comet exploded over what is now Cincinnati around 1,500 years ago, raining fire over the area and destroying villages and farm fields, supposedly resulting in the rapid decline of the ancient Indigenous Hopewell culture.

- www.biblicalarchaeology.org Luke’s Journey to Jerusalem Motif

What works of Greek literature influenced Luke—the author of the New Testament books of Luke and Acts—when he was writing? Luke and Acts should be

Did ancient Greek literature influence the writing of Luke’s Gospel? Image: Public Domain.

What works of Greek literature influenced Luke—the author of the New Testament books of Luke and Acts—when he was writing?

Luke and Acts should be seen as a single two-part work, two volumes of a historical monograph.1 This is shown by many features in both volumes, including chronological synchronisms and the preface in Luke 1:1–4. According to that preface, Luke wrote these books to Theophilus, a person of high status deserving the title of “noble” and probably his patron.

-

The Mystery of the Isle of Pines Mounds: How did 10,000 year old concrete cubes turn up on a remote island in the South Pacific?

www.ancient-origins.net The Isle of Pines Mounds: A South Pacific Mystery Solved?A small, picturesque, island in the French territory of New Caledonia hides a mystery that continues to defy rational explanation. More than 400 grass-covered mounds, averaging two or three meters in height, dot the Isle of Pines.

cross-posted from: https://kbin.social/m/13thFloor/t/325091

> A small, picturesque, island in the French territory of New Caledonia hides a mystery that continues to defy rational explanation. More than 400 grass-covered mounds, averaging two or three meters in height, dot the Isle of Pines. At first glance, these “tumuli,” as they are termed by scholars, look unremarkable. But a handful of excavations in 1959-60 revealed what lies hidden inside them - mysteries that still confound archaeologists and historians, who as recently as 2015 termed them “a kind of archaeological nightmare.” > > Nothing resembling these structures has been discovered anywhere else, except a small number on the main island of the country. Every attempt so far by archaeologists and historians to explain why they were built, and by whom, has failed - spectacularly - and the current mainstream theory only works if we ignore what the excavations have uncovered. > > The first puzzle is that inside each rounded mound of iron gravel and soil sits a large and very heavy cube of solid, high-quality, concrete. These blocks average 2 - 2.5 meters (6-8 feet) high. Carbon dating of snail shells attached to the outside of the concrete suggest it was made as far back as 10,000-12,000 years ago - many millennia before concrete was first manufactured anywhere in the world. > > Concrete technology in the South Pacific was actually unknown until the European arrival just two centuries ago. Not only that, this dating is thousands of years before any humans arrived in these islands. But there is more. > > A smooth, circular, shaft about 30 cm (1 foot) wide runs vertically down the center of each concrete block. Directly below the shaft, below ground, sits a large cone or top-shaped object made of iron, pointing down about 2 meters (6 feet) long. Rings of iron nuggets surround this object and also the core itself. The purpose of this metal object remains an enigma > > The first proper excavation took place in 1959, when locals on the Isle of Pines used one of the tumuli as a source of iron gravel for road repairs. This activity stopped, however, when the workers unexpectedly encountered its large concrete core that proved immune even to dynamite. > > French archaeologist Luc Chevalier hurried to investigate and then made the first - and most complete to date - excavation of a tumulus. This study was the first time the mysterious artifacts inside these structures were revealed and it provided samples for testing. > > However, just as the large cone-shaped metal object was exposed, the sides of the site threatened to collapse and the excavation ended as the team scrambled to safety. Perplexed by what the dig had revealed, Chevalier continued his research back in Noumea. He later investigated several tumuli on the mainland, which had also been destroyed or damaged, but did not resume the excavation on the Isle of Pines. Chevalier published his findings and a long list of unresolved questions in 1963. His original report (in French) can be readily accessed online . > > Before this took place, however, researchers and writers had begun speculating that this huge building project on a remote, isolated, island might represent the work of an unknown advanced civilization long ago, perhaps visiting from Japan or Asia, or a mythical kingdom such as Mu, Lemuria, or Atlantis. Even a visiting extraterrestrial civilization was proposed as a possibility. > > One of the more insightful conclusions came in a 1949 paper by the French geologist Jacques Avias. Without being more specific, he proposed a series of ancient arrivals in the southern Pacific, predating the Melanesians, concluding “…at least the following hypothesis can be put forward: a civilization …preceded the present Kanak civilization…this civilization had a Neolithic industry more advanced than the indigenous people.” > > It was not long before conservative thinking replaced such exotic ideas with more acceptable, down-to-earth, possibilities. The most enduring of them was that the mounds were actually made by long extinct giant megapode birds, to hatch their eggs in. It was suggested that the birds kicked up the soil until it formed a mound where eggs could be laid, warmed by decaying vegetation placed by the birds in the hole. Initially, the concrete core was explained away as the wholly natural action of microorganisms, tiny globules of calcite in the soil somehow binding rocks and debris together. > > Subsequently, a refinement of the theory proposed that the megapodes tidily excreted into the hole in the top of the mound, the feces becoming the heating agent for the eggs. Over time, the bird droppings are presumed to have fossilized and become the “cement” found today. Although chemical analysis established early on that the concrete core had none of the elements found in guano, many scholars and historians uncritically accepted this fiction as it did not challenge the accepted dates for human arrivals in the islands of New Caledonia. > > The avian theory was dealt a fatal blow in March 2016 with publication of a paper by a group led by an Australian-based paleozoologist, Trevor H. Worthy. After noting the obvious implications of the complete absence of any shell fragments in or near the tumuli, the paper reported that skeletal remains of the megapodes established rather conclusively that the birds were not, in fact, physically equipped for any type of mound building and particularly not mounds on the scale found in New Caledonia. > > Instead, in their paper Worthy and his team made their own proposal to explain the tumuli’s origins, suggesting that some “interplay between vegetation and erosion” somehow combined to erode the soil into the shapes we see today. It was a rather short-lived idea. > > The following year, in 2017, leading French archaeologist, Louis Lagarde, based in Noumea, published a landmark paper, “Were those mysterious mounds really for the birds?” that convincingly brought down the final curtain on the megapode theory. This, of course, was a tremendous step forward; by arguing that the tumuli were made by people, not by birds or curious weather, Lagarde seemed to open the door to more sensible explanations. Such did not prove to be the case. > > Despite this promising development and the admission that no bones, human or otherwise, have ever been found inside these mounds, Lagarde then claimed that the tumuli were, after all, merely burial mounds constructed by the local population over the last 2,000 or so years. He explained the lack of bones by proposing that over the centuries soil acidity and some undefined “exposure to the elements” had corroded them completely away. > > Most stunningly, despite his own well documented personal field experience and first-hand knowledge to the contrary, he went on to claim that the tumuli contain no archaeological materials! With that single statement, the concrete cores, the rings of iron nodules carefully placed around them, the perfectly circular shafts in the center of the cores, and the large metal cone-shaped object beneath it were all dismissed. > > Questions Going Beyond the Mainstream > > By now, the reader has probably noticed that all the mainstream “explanations” have had one thing in common: to make their case they have had to ignore what is actually inside the tumuli. This latest theory has had to do the same. Surely it will have future historians and scientists scratching their heads about the state of 21st century archaeology, in the South Pacific at least. > > And there, so far as consensus thinking is concerned, the matter rests. But the questions raised by French archaeologist Louis Chevalier after making that first excavation still seek answers: > > Who were the builders? Where did their ability to make high-quality concrete come from at a time when this technology was unknown? Where did they go? > > What possible motivation or purpose could cause people to invest so much effort to erect more than 400 of these structures [each averaging a volume of 500 cubic meters]? > > Why did such a massive effort leave no other traces - no tools, bones, charcoal, pottery, or other cultural artifacts - either within the tumulus or around it? > > Why did they not use this concrete-making ability to construct other works - their houses and other important buildings, their burials, and their sacred places? > > Finally, why was the ability to manufacture such a useful material as concrete not exported to other islands? Why was it not passed down to later people? Indeed, why did this ability not arise elsewhere in the region? > > Revealing the Construction Sequence > > Full answers to these questions remain to be found, but the author’s investigations in New Caledonia since 2017 have already made some things clear. This has included having new chemical analysis in Australia of the coral-based concrete. The latest technology available has confirmed the results reported in the pioneering studies. > > Close examinations of the tumulus excavated by Chevalier revealed features that his team had missed. This allowed a minimal construction sequence to be hypothesized, requiring at least 9 distinct stages to produce a single tumulus and an enormous amount of concrete to form the core. Of course, all this had to be repeated hundreds of times to create the structures we see today. > > The nine stages required, at a minimum, to erect each tumulus based on what excavation has already revealed. (Author provided) > > The nine stages required, at a minimum, to erect each tumulus based on what excavation has already revealed. (Author provided) > Parts of the Mystery at the Isle of Pines are Solved > > Simple engineering logic tells us what the purpose was for all this effort - the tumuli were built to stabilize - to an exceptionally high degree - some type of pylon or pillar in their shafts , but we do not yet know the purpose for the pylon itself. What did it support? Why did it have to be so rigid? And, as none remain today, what happened to the hundreds of pylons? > > Other pieces of the puzzle falling into place include the fact that nothing to date suggests that the tumuli construction took place over an extended period where we would expect to see improvements, improvisations, or the development of different styles. Everything suggests a one-time concentrated effort. > > Only two of the Paita tumuli on the main island preserve any trace - surplus raw material - of the construction process and, just possibly, of a stage of early experimentation with local materials. If so, we can speculate that the silica-based process may have been abandoned in favor of the iron resources readily available on the Isle of Pines. > > A tantalizing new question has also risen: the Isle of Pines is dominated by the “Iron Plateau,” so named for the abundance of iron in the form of gravel and nuggets; could this have anything to do with why the tumuli builders chose to build there? Is this a hint that some type of advanced technology was involved? > > Determining all this is now the challenge going forward. Ascertaining the function of the cone-shaped metal object beneath the shaft may offer the most promising line of future investigation. More work is obviously needed to resolve the mystery, but it will require people able to accept archaeological realities and who have open minds, not merely gate-keepers for outdated concepts.

-

Letter From Albania - A Road Trip Through Time

www.archaeology.org A Road Trip Through Time - Archaeology MagazineAs a new pipeline cuts its way through the Balkans, archaeologists in Albania are grabbing every opportunity to expose the country’s history—from the Neolithic to the present

As a new pipeline cuts its way through the Balkans, archaeologists in Albania are grabbing every opportunity to expose the country’s history—from the Neolithic to the present.

In modern Albania, the mélange of historical cultures is packed so densely they often seem to collide. The national E852 highway follows the same bank of the Shkumbin River as an ancient highway, the Via Egnatia, which was first traveled by Roman soldiers around 200 B.C. The road was modernized and maintained for centuries thereafter, and it became the main thoroughfare between Constantinople and the Adriatic, facilitating communication and trade between Rome and the eastern lands of the empire. Today, luxury Mercedes swerve between transcontinental bicyclists taking in the lush Mediterranean landscape and donkey carts hauling towering piles of forage. The route winds gently past medieval Ottoman Turkish bridges and white obelisks from the Communist era immortalizing partisan battles fought during World War II. Scrappy tobacco fields and mounds of hay and cornstalks line the route, planted and stacked by hand, much as they have been for centuries.

This primary ancient east-west artery of the Balkan Peninsula parallels, just to the south, another major European infrastructure project, one being built today: the Trans Adriatic Pipeline. The project, known as TAP, is laying 545 miles of pipe through northern Greece and Albania and under the Adriatic Sea, connecting existing Italian and Turkish pipelines to deliver Caspian gas to Europe by 2020. Perhaps counterintuitively, the massive construction project looks set to give an enormous boost to the study and preservation of Albania’s cultural heritage. During the Cold War, the hard-line Stalinist regime kept the country one of the world’s most isolated, and now this Maryland-sized country of three million is one of Europe’s poorest.

TAP’s resources are enormous by local standards—and could turn out to be the single greatest injection of money and know-how for archaeological exploration ever seen in Albania. The overall budget for TAP is $5.3 billion and about a quarter of the pipeline’s total length will sit in Albania. Lorenc Bejko, a prehistorian by trade who is the head of the archaeology department at Tirana University and a senior cultural heritage adviser for TAP in Albania, estimates that ordinarily the annual spending by all Albanian institutions combined on archaeological fieldwork doesn’t surpass $100,000. According to the project agreement, all management of the impact on Albania’s cultural heritage—including construction monitoring, excavation, preservation, development of management plans, scientific analysis, and even scientific publications—is controlled by Albanian government institutions and paid for by TAP. These activities are worth millions of dollars.

The odd geographical focus of the intensive TAP-funded archaeological work—a lateral route across the country 133 miles long, 124 feet wide, and typically a foot deep—coincides with the so-called right-of-way zone where the pipe will be buried. A rich variety of unrelated and unexpected ancient sites is being uncovered there: Neolithic settlements from Europe’s earliest farmers, along with Roman, Byzantine, and Ottoman sites. Turan, a site used for almost 2,000 years, yielded one of the oldest known cemeteries in Albania, dating back to 700 B.C. Ottoman cemeteries have also been found. And a picturesque hilltop settlement near the village of Peshtan, inhabited from the early Byzantine to the late Ottoman periods, has a cobbled street connecting a Turkish bath, a sixth-century Christian church, and several substantial houses with views of the valley below.