-

Happy Indeed Are the Arahants (SN 22.76)

This teaching is from the section The Planes of Realization from "In the Buddha's Words" by Bhikkhu Bodhi.

> The Buddha explains how one becomes the perfected one, an arahant, and shares verses on their qualities.

At Sāvatthi.

"Form, bhikkhus, is impermanent. What is impermanent is suffering; what is suffering is not-self; what is not-self should be seen as, 'This is not mine, I am not this, this is not my self,' — thus it should be seen with right wisdom as it really is.

Feeling, bhikkhus, is impermanent. What is impermanent is suffering; what is suffering is not-self; what is not-self should be seen as, 'This is not mine, I am not this, this is not my self,' — thus it should be seen with right wisdom as it really is.

Perception, bhikkhus, is impermanent. What is impermanent is suffering; what is suffering is not-self; what is not-self should be seen as, 'This is not mine, I am not this, this is not my self,' — thus it should be seen with right wisdom as it really is.

Volitional formations, bhikkhus, are impermanent. What is impermanent is suffering; what is suffering is not-self; what is not-self should be seen as, 'This is not mine, I am not this, this is not my self,' — thus it should be seen with right wisdom as it really is.

Consciousness, bhikkhus, is impermanent. What is impermanent is suffering; what is suffering is not-self; what is not-self should be seen as, 'This is not mine, I am not this, this is not my self,' — thus it should be seen with right wisdom as it really is.

Seeing thus, bhikkhus, the learned noble disciple becomes disenchanted with form, disenchanted with feeling, disenchanted with perception, disenchanted with volitional formations, and disenchanted with consciousness. Becoming disenchanted, they become dispassionate; through dispassion, they are liberated. When liberated, there is the insight that 'I am liberated.'"

He knows: 'Re-birth is ended, the spiritual life has been lived, what had to be done has been done, there is no more coming to any state of being.' Bhikkhus, in all the realms of beings, in all the worlds, these are highest, these are the foremost, namely, the arahants."

The Blessed One said this. Having spoken, the Well-Gone One, the Teacher, further spoke these words:

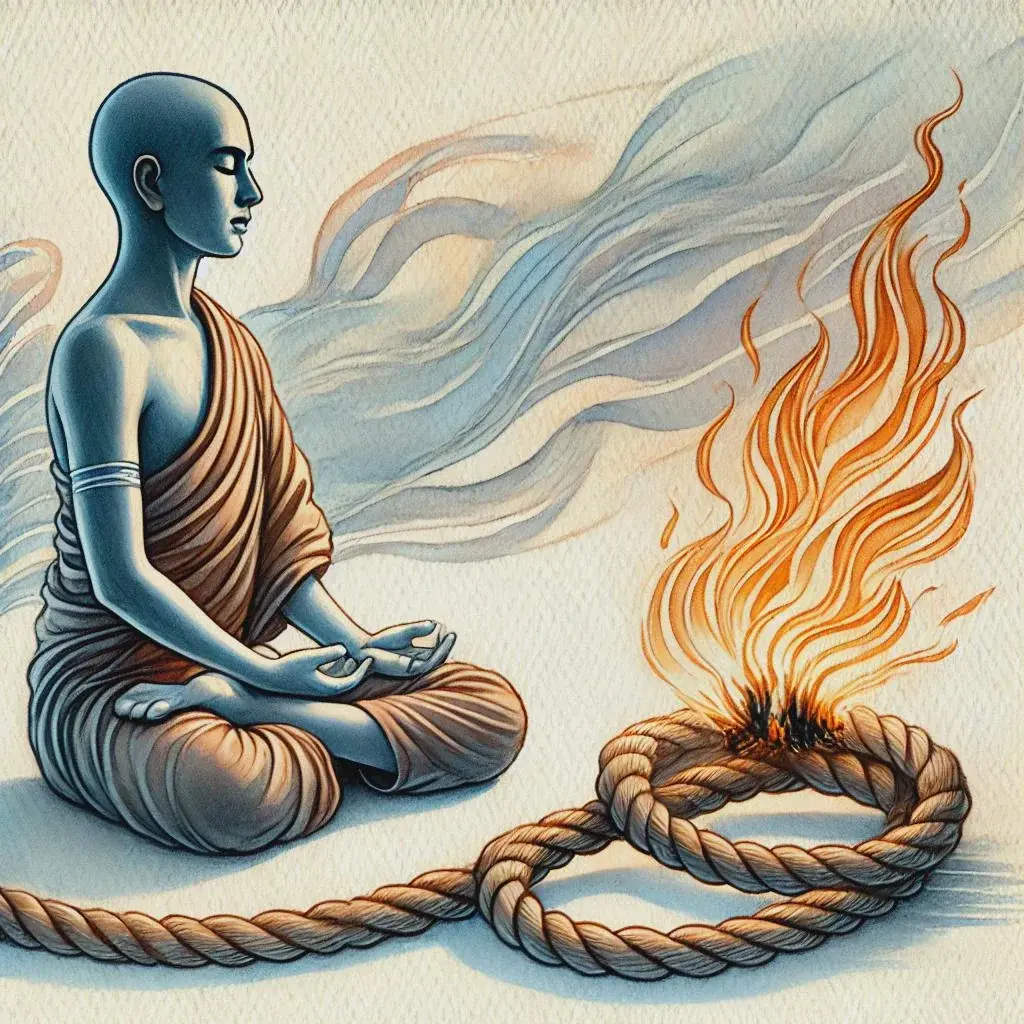

"Truly at ease are the arahants, for craving is no longer found in them; The conceit of 'I am' is cut off, and the net of delusion is torn apart.

Having arrived at the unperturbed, their minds are serene; In the world, they're untainted, they have become noble, free from defilements.

Having fully understood the five aggregates, they dwell in the true nature of things; Praiseworthy are these noble beings, true-born children of the Buddha.

Endowed with the seven elements of awakening, Well-trained in the three trainings; These great heroes wander freely, Having abandoned the causes of fear and dread.

Endowed with the ten factors, these great beings are deeply composed; Indeed, they are the foremost in the world, for craving is no longer found in them.

The wisdom of the non-learner has arisen, this is the final accumulation; It is the heartwood of the spiritual life, in which there is no further dependence.

They do not waver in any way, fully liberated from renewed existence; They have attained the state of self-control, these are the conquerors in the world.

Above, across, and below, no attachment is found in them; They roar the lion's roar, the Buddhas, unsurpassed in the world."

------

While it not possible to conceptually know the experience of one abiding in Nibbāna (enlightenment), it is helpful to clear any misperceptions that one may have about it and the qualities of an Arahant (an enlightened being).

One typically starts out with doubt about enlightenment and the possibility of attaining it for oneself, and if this is where you are, that's okay. You can harness this doubt to create an inquisitive mind - to learn, reflect and apply the teachings in practice and then see if the beneficial qualities of mind are arising and growing, and if your relationships are improving. You would like both to be improving and then, it's only a matter of continued practice till it becomes easy, automatic and second nature that this doubt dissolves to never arise again.

Related Teachings:

The Buddha and the Arahant (SN 22.58) - The Buddha shares the similarities and differences between him and another liberated by wisdom.

The trainee and the Arahant (SN 48.53) - Trainee here is a reference to someone who is a stream-enterer but not an Arahant. The Buddha is sharing this teaching to help an individual see where they're on the path.

Nine things an Arahant is incapable of doing (AN 9.7) - The Buddha explains to Sutavā, the wanderer, that an arahant is incapable of transgressing in nine ways.

33 Synonyms for Nibbāna (from SN 43.12 - 43.44) - This compilation of similar teachings is an invitation to broaden one's personal understanding of what the state of Nibbāna is.

-

Causes for the arising and expansion of the five hindrances (AN 1.11 - 20)

1.11

"Bhikkhus, I do not see any other single quality that causes unarisen sensual desire to arise, or arisen sensual desire to increase and expand, as a beautiful mental image. Bhikkhus, when one does not wisely attend to the sign of the beautiful, unarisen sensual desire arises, and arisen sensual desire increases and expands."

1.12

"Bhikkhus, I do not see any other single quality that causes unarisen ill-will to arise, or arisen ill-will to increase and expand, as an aversive mental image. Bhikkhus, when one does not wisely attend to the sign of resistance, unarisen ill-will arises, and arisen ill-will increases and expands."

1.13

"Bhikkhus, I do not see any other single quality that causes unarisen dullness and drowsiness to arise, or arisen dullness and drowsiness to increase and expand, as dissatisfaction, laziness, yawning, passing out after a meal, and sluggishness of mind. Bhikkhus, when the mind is sluggish, unarisen dullness and drowsiness arises, and arisen dullness and drowsiness increases and expands."

1.14

"Bhikkhus, I do not see any other single quality that causes unarisen restlessness and worry to arise, or arisen restlessness and worry to increase and expand, as an unsettled mind. Bhikkhus, when the mind is unsettled, unarisen restlessness and worry arises, and arisen restlessness and worry increases and expands."

1.15

"Bhikkhus, I do not see any other single quality that causes unarisen doubt to arise, or arisen doubt to increase and expand, as unwise attention. Bhikkhus, when one does not wisely attend, unarisen doubt arises, and arisen doubt increases and expands."

1.16

"Bhikkhus, I do not see any other single quality that prevents unarisen sensual desire from arising, or causes arisen sensual desire to be abandoned, as an unattractive mental image. Bhikkhus, when one wisely attends to the sign of the unattractive, unarisen sensual desire does not arise, and arisen sensual desire is abandoned."

1.17

"Bhikkhus, I do not see any other single quality that prevents unarisen ill-will from arising, or causes arisen ill-will to be abandoned, as the release of mind through loving-kindness. Bhikkhus, when one wisely attends to the release of mind through loving-kindness, unarisen ill-will does not arise, and arisen ill-will is abandoned."

1.18

"Bhikkhus, I do not see any other single quality that prevents unarisen dullness and drowsiness from arising, or causes arisen dullness and drowsiness to be abandoned, as taking initiative, persistence, and continuous effort. Bhikkhus, when one is energetic, unarisen dullness and drowsiness do not arise, and arisen dullness and drowsiness are abandoned."

1.19

"Bhikkhus, I do not see any other single quality that prevents unarisen restlessness and worry from arising, or causes arisen restlessness and worry to be abandoned, as settling of the mind. Bhikkhus, when the mind is settled, unarisen restlessness and worry do not arise, and arisen restlessness and worry are abandoned."

1.20

"Bhikkhus, I do not see any other single quality that prevents unarisen doubt from arising, or causes arisen doubt to be abandoned, as wise attention. Bhikkhus, when one wisely attends, unarisen doubt does not arise, and arisen doubt is abandoned."

------

Wise attention (1.20) is reflecting and reviewing on the mental qualities of the four noble truths, the five hindrances, the seven factors of enlightenment, on the arising and passing of the five aggregates dependent on sense contact. Unwise attention (1.15) is having craving or displeasure with regard to the world, either in the present, or in reviving the past, or in building hope on the future.

Related Teachings:

Nutriment for Arising of Hindrances and Factors of Awakening (SN 46.51) - The Buddha explains the nutriment and the lack of nutriment for the five hindrances and the seven factors of awakening.

Hindrances as different bowls of water (SN 46.55) - The brahmin Saṅgārava asks why sometimes verses stay in memory while other times they don’t. The Buddha replies that it is due to the presence of either the hindrances or awakening factors. He gives a set of similes illustrating each of the hindrances with different bowls of water.

The five hindrances weaken wisdom | simile of side-channels weakening a river's flow (AN 5.51) - The five hindrances weaken wisdom like side-channels weaken a river’s flow.

-

Along the Current (AN 4.5)

> The Buddha describes the four types of persons found in the world - those who go with the current, those who go against the current, those who are steady, and those who have crossed over, standing on the firm ground, arahants.

And what, bhikkhus, is the person who goes with the current? Here, bhikkhus, a certain person engages in sensual pleasures and performs unwholesome actions. This is called the person who goes with the current.

And what, bhikkhus, is the person who goes against the current? Here, bhikkhus, a certain person does not indulge in sensual pleasures and does not perform unwholesome actions. Even with suffering, sorrow, tearful face, and crying, they live a fully pure spiritual life. This is called the person who goes against the current.

And what, bhikkhus, is the person who is steady? Here, bhikkhus, a certain person, with the complete wearing away of the five lower fetters, becomes spontaneously reborn and there attains final Nibbāna, not subject to returning from that world. This is called the person who is steady.

And what, bhikkhus, is the person who has crossed over, standing on the shore, an awakened one? Here, bhikkhus, a certain person, through the complete wearing away of the taints, has attained the taint-free release of mind and release by wisdom, having realized it by direct knowledge in this very life, and lives having attained it. This is called the person who has crossed over, standing on the shore, a brāhmin.

Indeed, bhikkhus, these four persons exist in the world.

> Whoever are unrestrained in sensual pleasures, not free from passion, enjoying sensual pleasures here; They go again and again to birth and aging, overcome by craving, they go with the current.

> Therefore, a wise person established in mindfulness here, not engaging in sensual pleasures and unwholesome actions; Should abandon sensual pleasures even if it's painful, They call such a person one who goes against the current.

> Whoever has abandoned the five defilements, perfected in training and not subject to decline, Attained mastery of the mind and with composed faculties, They indeed are called a steady person.

> One who has comprehended things subtle and gross, scattered them up, so they're gone and exist no more; They indeed are a sage, having lived the spiritual life, and reached the world's end, they are called 'one who has gone beyond'."

-------

The process of letting go of sensual pleasures during the training can perhaps be painful or with sorrow, and hence, the Buddha describes this as a person going against the current.

Related Teachings:

Sensuality is subject to time, of much stress (SN 1.20) - A deity tries to persuade a monk to first enjoy sensual pleasures and then go forth.

Intoxicated with Vanity of Youth, Health and Life (AN 3.31) - In this teaching, the Buddha recounts his delicate bringing up, and warns on the three intoxications: of youth, health, and life.

Allure and Drawbacks of Desiring Pleasure (Snp 4.1) - This verse succinctly captures the allure and the drawbacks of engaging in sense-desires.

-

Difficult To Guard And Restrain (DhP 33)

> Unstable and unsteady is the mind, difficult to guard and restrain; The wise one makes it straight, like a fletcher straightens an arrow.

-- DhammaPada Verse 33

------

Related Teachings:

The well-composed Mind (AN 9.26) - Venerable Sāriputta clarifies on a teaching on how enlightenment is to be verified. He shares a visual simile of the stone pillar.

On Wise Attention | A Trainee - First (ITI 16) - Wise attention is very helpful to a trainee to awaken to enlightenment.

Steadying the mind against the poisons of greed, hate and delusion (AN 4.117) - Practice diligence, mindfulness, and guarding of the mind in these four situations.

-

Seven factors of awakening (SN 46.3)

>The Buddha explains the benefits of associating with virtuous persons and how the development of the seven awakening factors comes to be.

"Bhikkhus, those bhikkhus who are accomplished in virtue, collectedness, wisdom, liberation, and the wisdom and vision of liberation — I say that seeing such bhikkhus is of great benefit; listening to them is of great benefit; approaching them is of great benefit; attending upon them is of great benefit; recollecting them is of great benefit; and even going forth with \[faith in\] them is of great benefit. Why is that so? Because, bhikkhus, after hearing the Dhamma from such bhikkhus, one withdraws in two ways: by bodily seclusion and by mental seclusion. Dwelling thus secluded, one remembers and reflects on that Dhamma.

Bhikkhus, when a bhikkhu, dwelling thus secluded, remembers and reflects on that Dhamma, at that time, the awakening factor of mindfulness is aroused in him. At that time, the bhikkhu develops the awakening factor of mindfulness. At that time, the awakening factor of mindfulness reaches fulfillment through meditation in him. Dwelling thus mindfully, he examines that Dhamma with wisdom, investigates, and thoroughly reflects upon it.

Bhikkhus, when a bhikkhu, dwelling thus mindfully, examines that Dhamma with wisdom, investigates, and thoroughly reflects upon it, at that time, the awakening factor of investigation of phenomena is aroused in him. At that time, the bhikkhu develops the awakening factor of investigation of phenomena. At that time, the awakening factor of investigation of phenomena reaches fulfillment through meditation in him. For him, as he examines that Dhamma with wisdom, analyzing, and engaging in thorough reflection, unwavering energy is aroused.

Bhikkhus, at that time, when a bhikkhu, examining that Dhamma with wisdom, analyzing, and engaging in thorough reflection, unwavering energy is aroused in him. At that time, the awakening factor of energy is aroused in him. At that time, the bhikkhu develops the awakening factor of energy. At that time, the awakening factor of energy reaches fulfillment through meditation in him. For him with aroused energy, non-material joy arises.

Bhikkhus, at that time, when non-material joy arises in a bhikkhu with aroused energy, the awakening factor of joy is aroused in him. At that time, the bhikkhu develops the awakening factor of joy. At that time, the awakening factor of joy reaches fulfillment through meditation in him. For one with a joyful mind, the body becomes tranquil, and the mind becomes tranquil as well.

Bhikkhus, at that time, when the body of a bhikkhu with a joyful mind becomes tranquil and the mind becomes tranquil, the awakening factor of tranquility is aroused in him. At that time, the bhikkhu develops the awakening factor of tranquility. At that time, the awakening factor of tranquility reaches fulfillment through meditation in him. For one whose body is tranquil and at ease, the mind becomes collected.

Bhikkhus, at that time, when the mind of a bhikkhu, whose body is tranquil and at ease, becomes collected, the awakening factor of collectedness is aroused in him. At that time, the bhikkhu develops the awakening factor of collectedness. At that time, the awakening factor of collectedness reaches fulfillment through meditation in him. With the mind thus collected, he thoroughly observes with equanimity.

Bhikkhus, at that time, when a bhikkhu thoroughly observes with equanimity the mind that is thus collected, the awakening factor of equanimity is aroused in him. At that time, the bhikkhu develops the awakening factor of equanimity. At that time, the awakening factor of equanimity reaches fulfillment through meditation in him.

Bhikkhus, when the seven awakening factors are developed and practiced often in this way, seven fruits and seven benefits can be expected. What are the seven fruits and seven benefits?

- One attains final knowledge \[of the complete wearing away of the taints\] in this very life.

- If not in this very life, then one attains final knowledge at the time of death.

- If one does not attain final knowledge in this very life, and if one does not attain final knowledge at the time of death, then with the complete wearing away of the five lower fetters, one becomes an attainer of final Nibbāna in-between.

- If one does not attain final knowledge in this very life, and if one does not attain final knowledge at the time of death, and if one does not become an attainer of final Nibbāna in-between, then with the complete wearing away of the five lower fetters, one becomes an attainer of final Nibbāna upon landing \[in the next life\].

- If one does not attain final knowledge in this very life, and if one does not attain final knowledge at the time of death, and if one does not become an attainer of final Nibbāna in-between, and if one does not become an attainer of final Nibbāna upon landing, then with the complete wearing away of the five lower fetters, one becomes an attainer of final Nibbāna without effort.

- If one does not attain final knowledge in this very life, and if one does not attain final knowledge at the time of death, and if one does not become an attainer of final Nibbāna in-between, and if one does not become an attainer of final Nibbāna upon landing, and if one does not become an attainer of final Nibbāna without effort, then with the complete wearing away of the five lower fetters, one becomes an attainer of final Nibbāna with effort.

- If one does not attain final knowledge in this very life, and if one does not attain final knowledge at the time of death, and if one does not become an attainer of final Nibbāna in-between, and if one does not become an attainer of final Nibbāna upon landing, and if one does not become an attainer of final Nibbāna without effort, and if one does not become an attainer of final Nibbāna with effort, then with the complete wearing away of the five lower fetters, one becomes one bound upstream, heading towards the Akaniṭṭha realm.

Bhikkhus, when the seven awakening factors are developed and practiced often in this way, these seven fruits and seven benefits can be expected."

-

A tamed mind leads to ease (DhP 35 - 37)

DhP 35:

>Tricky to pin down and swift, landing wherever it wants; The taming of the mind is good, for the tamed mind leads to ease.

DhP 36:

>The mind is very subtle and hard to see, landing wherever it wants; The wise one should guard the mind, for a guarded mind leads to ease.

DhP 37:

>Wandering far and moving on its own, immaterial, dwelling in a cave (hiding place); Those who restrain the mind, will be freed from Māra's bonds.

---

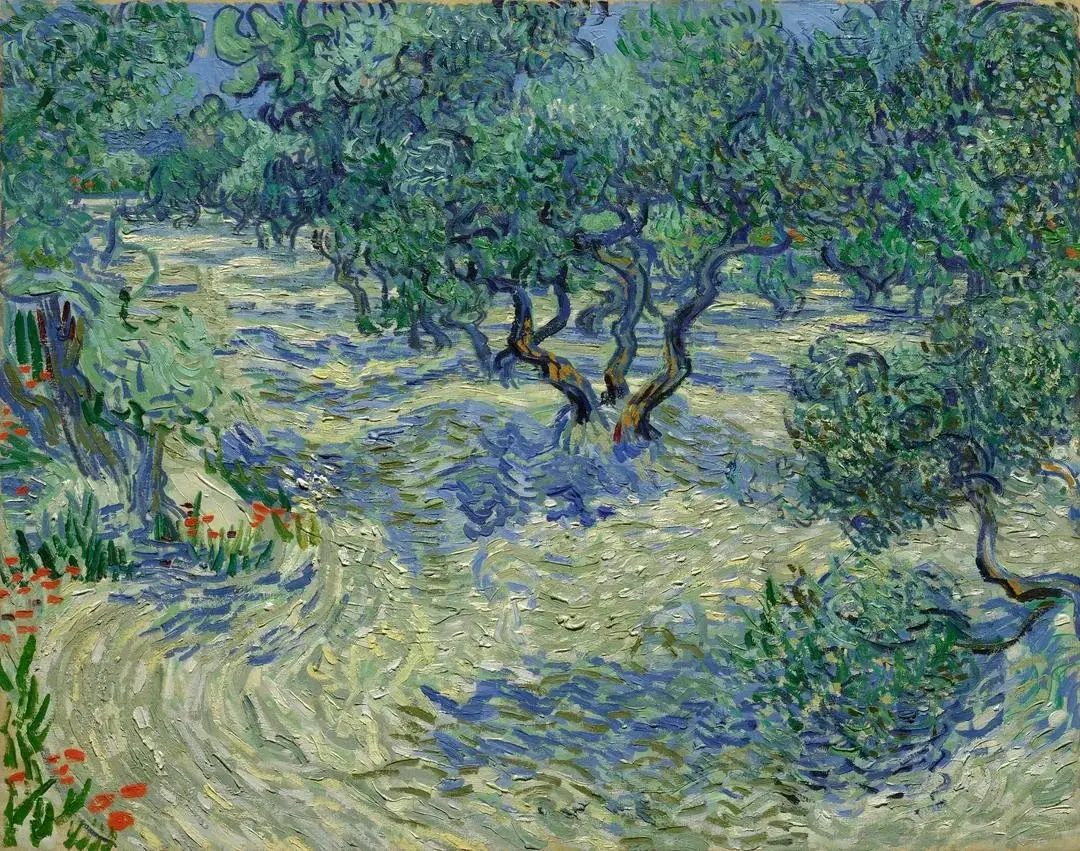

Picture: September Flowers, Jeremy Galton

-

A detailed analysis of the four bases of psychic ability (SN 51.20)

>A detailed analysis of the four bases of psychic ability - collectedness arising from aspiration, energy, purification of mind, and investigation. These four bases are noble, and leads one who cultivates them to become mighty, powerful, to full understanding of the five higher fetters, to liberation.

"Bhikkhus, these four bases of psychic ability, when developed and frequently practiced, are of great fruit and benefit.

"How, bhikkhus, are the four bases of psychic ability developed and frequently practiced so that they are of great fruit and great benefit? Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu develops the basis of psychic ability that is endowed with collectedness arising from aspiration (a goal, an interest, an objective, i.e. a wholesome desire) and accompanied by intentional effort thus: 'My aspiration will not be too slack, nor too intense, nor inwardly inhibited, nor outwardly scattered. He dwells continuously aware: 'As before, so after; as after, so before; as below, so above; as above, so below; as by day, so by night; as by night, so by day.' Thus with a mind that is clarified and unconfined, he develops a radiant mind."

A bhikkhu develops the base of psychic ability that is endowed with collectedness arising from energy and accompanied by intentional effort thus: 'My energy will not be too slack, nor too intense, nor inwardly inhibited, nor outwardly scattered.' He dwells continuously aware: 'As before, so after; as after, so before; as below, so above; as above, so below; as by day, so by night; as by night, so by day.' Thus with a mind that is clarified and unconfined, he develops a radiant mind.

A bhikkhu develops the base of psychic ability that is endowed with collectedness arising from \[purification of\] mind and accompanied by intentional effort thus: 'My mind will not be too slack, nor too intense, nor inwardly inhibited, nor outwardly scattered.' He dwells continuously aware: 'As before, so after; as after, so before; as below, so above; as above, so below; as by day, so by night; as by night, so by day.' Thus with a mind that is clarified and unconfined, he develops a radiant mind.

A bhikkhu develops the base of psychic ability that is endowed with collectedness arising from investigation (consideration, reflection, and examination) accompanied by intentional effort thus: 'My investigation will not be too slack, nor too intense, nor inwardly inhibited, nor outwardly scattered.' He dwells dwells continuously aware: 'As before, so after; as after, so before; as below, so above; as above, so below; as by day, so by night; as by night, so by day.' Thus with a mind that is clarified and unconfined, he develops a radiant mind.

Analysis of Aspiration

Bhikkhus, what is an aspiration that is too slack? Bhikkhus, aspiration that is accompanied by laziness and associated with laziness — this is called aspiration that is too slack.

Bhikkhus, what is an aspiration that is too intense? Bhikkhus, aspiration that is accompanied by restlessness and associated with restlessness — this is called aspiration that is too intense.

Bhikkhus, what is an aspiration that is inwardly inhibited? Bhikkhus, aspiration that is accompanied by dullness and drowsiness and associated with dullness and drowsiness — this is called aspiration that is inwardly inhibited.

Bhikkhus, what is an aspiration that is outwardly scattered? Bhikkhus, aspiration that is outwardly scattered due to engagement with the five cords of sensual pleasure — this is called aspiration that is outwardly scattered.

And how, bhikkhus, does a bhikkhu dwell continuously aware: 'As before, so after; as after, so before'? Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu's mindfulness of before and after is well grasped, well attended to, well sustained, and well penetrated by wisdom. Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu dwells contemplating 'As before, so after; as after, so before.'

Bhikkhus, how does a bhikkhu dwell contemplating 'As below, so above; as above, so below'? Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu contemplates this very body from the soles of the feet upward and from the crown of the head downward, bounded by skin and full of various kinds of impurities: 'In this body there are hairs, body hairs, nails, teeth, skin, flesh, sinews, bones, bone marrow, kidneys, heart, liver, diaphragm, spleen, lungs, intestines, mesentery, stomach, feces, bile, phlegm, pus, blood, sweat, fat, tears, grease, saliva, snot, oil of the joints, and urine.' Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu dwells contemplating 'As below, so above; as above, so below.'

Bhikkhus, how does a bhikkhu dwell contemplating 'As by day, so by night; as by night, so by day'? Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu develops the base of psychic ability that is endowed with collectedness arising from aspiration, accompanied by an intention of continuous effort by day, and also by night, thus: 'My aspiration will not be too slack, nor too intense, nor inwardly inhibited, nor outwardly scattered.' He dwells contemplating 'As before, so after; as after, so before; as below, so above; as above, so below; as by day, so by night; as by night, so by day.' Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu dwells contemplating 'As by day, so by night; as by night, so by day.'

And how, bhikkhus, does a bhikkhu develop a mind that is clarified, unconfined and radiant? Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu's perception of brightness is well grasped, and his perception of day is well established. Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu develops a mind that is clarified, unconfined, and radiant."

Analysis of Energy

And what, bhikkhus, is energy that is too slack? Bhikkhus, energy that is accompanied by laziness and associated with laziness — this is called energy that is too slack.

And what, bhikkhus, is energy that is too intense? Bhikkhus, energy that is accompanied by restlessness and associated with restlessness — this is called energy that is too intense.

And what, bhikkhus, is energy that is inwardly inhibited? Bhikkhus, energy that is accompanied by dullness and drowsiness and associated with dullness and drowsiness — this is called energy that is inwardly inhibited.

And what, bhikkhus, is energy that is outwardly scattered? Bhikkhus, energy that is outwardly scattered due to engagement with the five cords of sensual pleasure — this is called energy that is outwardly scattered.

And how, bhikkhus, does a bhikkhu dwell continuously aware: 'As before, so after; as after, so before?' Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu's mindfulness of before and after is well grasped, well attended to, well sustained, and well penetrated by wisdom. Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu dwells contemplating 'As before, so after; as after, so before.'

And how, bhikkhus, does a bhikkhu dwell contemplating 'As below, so above; as above, so below?' Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu contemplates this very body from the soles of the feet upward and from the crown of the head downward, bounded by skin and full of various kinds of impurities: 'In this body there are hairs, body hairs, nails, teeth, skin, flesh, sinews, bones, bone marrow, kidneys, heart, liver, diaphragm, spleen, lungs, intestines, mesentery, stomach, feces, bile, phlegm, pus, blood, sweat, fat, tears, grease, saliva, snot, oil of the joints, and urine.' Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu dwells contemplating 'As below, so above; as above, so below.'

And how, bhikkhus, does a bhikkhu dwell contemplating 'As by day, so by night; as by night, so by day?' Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu develops the base of psychic ability that is endowed with collectedness arising from energy, accompanied by an intention of continuous effort by day, and also by night, thus: 'My energy will not be too slack, nor too intense, nor inwardly inhibited, nor outwardly scattered.' He dwells contemplating 'As before, so after; as after, so before; as below, so above; as above, so below; as by day, so by night; as by night, so by day.' Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu dwells contemplating 'As by day, so by night; as by night, so by day.'

And how, bhikkhus, does a bhikkhu develop a mind that is clarified, unconfined, and radiant? Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu's perception of brightness is well grasped, and his perception of day is well established. Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu develops a mind that is clarified, unconfined, and radiant.

Analysis of [Purification of] Mind

And what, bhikkhus, is a mind that is too slack? Bhikkhus, a mind that is accompanied by laziness and associated with laziness — this is called a mind that is too slack.

And what, bhikkhus, is a mind that is too intense? Bhikkhus, a mind that is accompanied by restlessness and associated with restlessness — this is called a mind that is too intense.

And what, bhikkhus, is a mind that is inwardly inhibited? Bhikkhus, a mind that is accompanied by dullness and drowsiness and associated with dullness and drowsiness — this is called a mind that is inwardly inhibited.

And what, bhikkhus, is a mind that is outwardly scattered? Bhikkhus, a mind that is outwardly scattered due to engagement with the five cords of sensual pleasure — this is called a mind that is outwardly scattered.

And how, bhikkhus, does a bhikkhu dwell continuously aware: 'As before, so after; as after, so before?' Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu's mindfulness of before and after is well grasped, well attended to, well sustained, and well penetrated by wisdom. Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu dwells contemplating 'As before, so after; as after, so before.'

And how, bhikkhus, does a bhikkhu dwell contemplating 'As below, so above; as above, so below?' Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu contemplates this very body from the soles of the feet upward and from the crown of the head downward, bounded by skin and full of various kinds of impurities: 'In this body there are hairs, body hairs, nails, teeth, skin, flesh, sinews, bones, bone marrow, kidneys, heart, liver, diaphragm, spleen, lungs, intestines, mesentery, stomach, feces, bile, phlegm, pus, blood, sweat, fat, tears, grease, saliva, snot, oil of the joints, and urine.' Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu dwells contemplating 'As below, so above; as above, so below.'

And how, bhikkhus, does a bhikkhu dwell contemplating 'As by day, so by night; as by night, so by day?' Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu develops the base of psychic ability that is endowed with collectedness arising from mind, accompanied by an intention of continuous effort by day, and also by night, thus: 'My mind will not be too slack, nor too intense, nor inwardly inhibited, nor outwardly scattered.' He dwells contemplating 'As before, so after; as after, so before; as below, so above; as above, so below; as by day, so by night; as by night, so by day.' Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu dwells contemplating 'As by day, so by night; as by night, so by day.'

And how, bhikkhus, does a bhikkhu develop a mind that is clarified, unconfined, and radiant? Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu's perception of brightness is well grasped, and his perception of day is well established. Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu develops a mind that is clarified, unconfined, and radiant.

Analysis of Investigation

And what, bhikkhus, is an investigation that is too slack? Bhikkhus, an investigation that is accompanied by laziness and associated with laziness — this is called an investigation that is too slack.

And what, bhikkhus, is an investigation that is too intense? Bhikkhus, an investigation that is accompanied by restlessness and associated with restlessness — this is called an investigation that is too intense.

And what, bhikkhus, is an investigation that is inwardly inhibited? Bhikkhus, an investigation that is accompanied by dullness and drowsiness and associated with dullness and drowsiness — this is called an investigation that is inwardly inhibited.

And what, bhikkhus, is an investigation that is outwardly scattered? Bhikkhus, an investigation that is outwardly scattered due to engagement with the five cords of sensual pleasure — this is called an investigation that is outwardly scattered.

And how, bhikkhus, does a bhikkhu dwell continuously aware: 'As before, so after; as after, so before?' Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu's mindfulness of before and after is well grasped, well attended to, well sustained, and well penetrated by wisdom. Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu dwells contemplating 'As before, so after; as after, so before.'

And how, bhikkhus, does a bhikkhu dwell contemplating 'As below, so above; as above, so below?' Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu contemplates this very body from the soles of the feet upward and from the crown of the head downward, bounded by skin and full of various kinds of impurities: 'In this body there are hairs, body hairs, nails, teeth, skin, flesh, sinews, bones, bone marrow, kidneys, heart, liver, diaphragm, spleen, lungs, intestines, mesentery, stomach, feces, bile, phlegm, pus, blood, sweat, fat, tears, grease, saliva, snot, oil of the joints, and urine.' Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu dwells contemplating 'As below, so above; as above, so below.'

And how, bhikkhus, does a bhikkhu dwell contemplating 'As by day, so by night; as by night, so by day?' Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu develops the base of psychic ability that is endowed with collectedness arising from investigation, accompanied by an intention of continuous effort by day, and also by night, thus: 'My investigation will not be too slack, nor too intense, nor inwardly inhibited, nor outwardly scattered.' He dwells contemplating 'As before, so after; as after, so before; as below, so above; as above, so below; as by day, so by night; as by night, so by day.' Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu dwells contemplating 'As by day, so by night; as by night, so by day.'

And how, bhikkhus, does a bhikkhu develop a mind that is clarified, unconfined, and radiant? Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu's perception of brightness is well grasped, and his perception of day is well established. Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu develops a mind that is clarified, unconfined, and radiant.

Thus developed and frequently practiced, bhikkhus, the four bases of psychic ability are of great fruit and great benefit.

Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu who has developed and frequently practiced the four bases of psychic ability experiences various kinds of psychic abilities: being one, he becomes many; being many, he becomes one; he appears and disappears; he passes through walls, enclosures, and mountains as though through space; he dives in and out of the earth as though it were water; he walks on water without sinking as though on solid ground; he flies through the air cross-legged like a bird with wings; he touches and strokes the sun and moon, so mighty and powerful; and he controls his body as far as the Brahmā world. Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu who has developed and frequently practiced the four bases of psychic ability, through the wearing away of the taints, attains and dwells in the taintless release of mind and release by wisdom, having realized it with direct knowledge in this very life."

------------

This is a fine-tuning instruction that one can use to refine their practice of the eightfold path. One can also investigate and to see whether success in any domain - spiritual or a worldly one, at the highest levels, comes through frequently practicing in the four bases of psychic abilities. If one has a view on manifestation, or on the power of desire, one can further their understanding by full understanding all the four bases needed.

-

Ugga, the householder of Vesālī (AN 8.21)

>Ugga, the householder of Vesālī is endowed with eight wonderful and marvelous qualities.

Once, the Blessed One was staying at Vesālī in the Great Wood, in the Hall with the Peaked Roof. There, the Blessed One addressed the bhikkhus: "Bhikkhus, remember Ugga the householder of Vesālī as being endowed with eight wonderful and marvelous qualities."

The Blessed One said this. Having spoken thus, the Well-Gone One rose from his seat and entered his dwelling.

Then, a certain bhikkhu, after dressing in the morning and taking his bowl and robe, approached the residence of Ugga the householder of Vesālī; having approached, he sat down on a prepared seat. Then, Ugga the householder of Vesālī approached that bhikkhu; having approached, he paid homage to the bhikkhu and sat down to one side. As Ugga the householder of Vesālī was seated to one side, the bhikkhu said to him:

"Householder, the Blessed One has declared that you are endowed with eight wonderful and marvelous qualities. What are they?"

"Venerable sir, I do not know what eight wonderful and marvelous qualities the Blessed One has declared that I possess. However, there are indeed eight wonderful and marvelous qualities found in me. Listen to it and pay close attention, I will speak."

"Yes, householder," the bhikkhu responded to Ugga the householder of Vesālī. Then Ugga the householder of Vesālī spoke thus:

- "When I first saw the Blessed One from afar, with just that sight itself, venerable sir, my mind became inspired with confidence in the Blessed One. This, venerable sir, is the first wonderful and marvelous quality that is found in me.

- Venerable sir, with a confident mind, I attended upon the Blessed One. The Blessed One gradually gave me a discourse, first on giving, then on virtue, and then on the heavens. He explained the dangers, degradation, and defilement of sensual pleasures and the benefit of renunciation. When the Blessed One knew that my mind was ready, receptive, free of hindrances, uplifted, and confident, he then expounded to me the distinctive teaching of the Buddhas: suffering, its arising, its cessation, and the path. Just as a clean cloth with no dark spots would perfectly absorb dye, so too, as I was sitting there, the stainless, immaculate Dhamma eye arose in me: 'Whatever is subject to arising, is subject to cessation.' Venerable sir, I then became one who has seen the Dhamma, who has attained the Dhamma, who has understood the Dhamma, who has deeply penetrated the Dhamma, having crossed beyond doubt, with no more uncertainty, self-assured, and independent of others in the Teacher's instruction. Right there, I went for refuge to the Buddha, the Dhamma, and the Sangha, and I undertook the training rules with celibacy as the fifth. This, venerable sir, is the second wonderful and marvelous quality that is found in me.

- Venerable sir, I had four young wives. I approached them and said: 'Sisters, I have undertaken the training rules with celibacy as the fifth. Whoever wishes may stay here and enjoy the wealth and perform meritorious deeds, or you may return to your own family. Or if there is another man you prefer, I will give you to him.' When I said this, my eldest wife replied: 'Give me to such and such a man, dear husband.' So, venerable sir, I called that man, and with my left hand I gave my wife to him, and with my right hand, I presented him with a ceremonial offering. Yet, venerable sir, even while parting with my young wife, I did not notice any alteration in my mind. This, venerable sir, is the third wonderful and marvelous quality that is found in me.

- Venerable sir, there is wealth in my family, and it is not withheld from those who are virtuous and of an upright nature. This, venerable sir, is the fourth wonderful and marvelous quality that is found in me.

- Venerable sir, when I attend upon a bhikkhu, I do so with proper respect, not without respect. This, venerable sir, is the fifth wonderful and marvelous quality that is found in me.

- Venerable sir, if that venerable one teaches me the Dhamma, I listen to it attentively, not carelessly. If he does not teach me the Dhamma, I teach him the Dhamma. This, venerable sir, is the sixth wonderful and marvelous quality that is found in me.

- It is not unusual for deities to come to me and announce: 'The Dhamma is well-expounded by the Blessed One, householder.' When this is said, venerable sir, I reply to those deities: 'Whether you deities say this or not, the Dhamma is indeed well-expounded by the Blessed One. However, venerable sir, I do not perceive any elation of mind because of this, thinking: 'Deities approach me, and I converse with them.' This, venerable sir, is the seventh wonderful and marvelous quality that is found in me.

- Venerable sir, regarding the five lower fetters taught by the Blessed One, I do not see anything within myself that has not been abandoned. This, venerable sir, is the eighth wonderful and marvelous quality that is found in me.

These, venerable sir, are the eight wonderful and marvelous qualities that are found in me. However, I do not know which eight wonderful and marvelous qualities the Blessed One declared that I am endowed with."

Then the bhikkhu, after taking alms food from the house of Ugga the householder of Vesālī, rose from his seat and departed. After his meal, the bhikkhu, having completed his alms round, approached the Blessed One; having approached, he paid homage to the Blessed One and sat down to one side. As he was sitting to one side, the bhikkhu reported to the Blessed One all of his conversation with Ugga the householder of Vesālī.

The Blessed One said, "Good, good, bhikkhu. As Ugga the householder of Vesālī rightly explained, in the same way, I declare that he is endowed with these eight wonderful and marvelous qualities. Bhikkhu, remember Ugga the householder of Vesālī as being endowed with these eight wonderful and marvelous qualities."

-

Gathering flowers with an attached mind (DhP 47)

>While gathering flowers, with an attached mind; Like a great flood sweeps away a sleeping village, so does death carry such a person away.

-- DhammaPada Verse 47

-

Meditation Tip: Removing Craving and Displeasure With Regard To The World

The Buddha's meditation guidance is to begin and then stay in the meditation session by removing any arising craving and displeasure with regard to the world, with continuous effort, fully aware, mindful.

> One way to do this is to bring a wholesome object to the mind: such as a memory of a time when you acted with pure generosity, expecting nothing in return.

When practiced, this has the effect of bringing the mind out of any hindrances, to unification, to collectedness, where now one can then practice per the breathing-mindfulness meditation guidance.

A regular practice of meditation clears the mind of obstructions

-

Upajjhāya sutta - Mentor (AN 5.56)

Then, a certain bhikkhu approached his own preceptor (mentor) and said: "Venerable sir, at present I feel as if my body is intoxicated, the directions seem unclear to me, the teachings do not spring to mind, complacency (dullness and drowsiness) completely occupies my mind, I do not find enjoyment in the spiritual life, and I have doubts about the teachings."

Then the preceptor taking his pupil with him, approached the Blessed One. After paying respects to the Blessed One, they sat down to one side. Once seated, the bhikkhu said to the Blessed One: "Venerable sir, this bhikkhu says: 'At present, I feel as if my body is intoxicated, the directions seem unclear to me, the teachings do not spring to mind, complacency completely occupies my mind, I do not find enjoyment in the spiritual life, and I have doubts about the teachings.'"

The Blessed One replied: "Indeed, bhikkhu, this happens when 1) one is not guarded in the sense faculties, 2) not applying moderation in eating, 3) not dedicated to wakefulness, 4) lacks insight into wholesome qualities, and 5) does not engage in the development of the awakening factors during the first and last watch of the night. As a result, the body feels as if intoxicated, the directions seem unclear, the teachings do not spring to mind, complacency completely occupies the mind, one does not find enjoyment in the spiritual life, and doubts about the teachings arise.

Therefore, bhikkhu, you should train yourself thus: 'I will be guarded in the sense faculties, apply moderation in eating, be dedicated to wakefulness, develop insight into wholesome qualities, and engage in the development of the awakening factors during the first and last watch of the night.' This is how you should train yourself."

Then, that bhikkhu, having been instructed by the Blessed One with this advice, rose from his seat, paid respects to the Blessed One, circumambulated him to the right, and departed.

Thereafter, that bhikkhu, living in seclusion, with diligence, continuous effort, and resoluteness, not long after, realized by personal knowledge and attained in that very life the unsurpassed culmination of the spiritual life for which sons of good families rightly go forth from the household life into homelessness.

He understood: "Birth is ended, the spiritual life has been lived, what had to be done has been done, there is no more coming to any state of being." And that bhikkhu became one among the arahants.

Then that bhikkhu, having attained arahantship, approached his preceptor and said: "Venerable sir, at present my body no longer feels as if intoxicated, the directions are clear to me, the teachings spring to mind, complacency no longer occupies my mind, I find enjoyment in the spiritual life, and I have no doubts about the teachings."

Then, taking his pupil with him, the preceptor approached the Blessed One. After paying respects to the Blessed One, they sat down to one side. Once seated, the preceptor said to the Blessed One: "Venerable sir, this bhikkhu says: 'At present, my body no longer feels as if intoxicated, the directions are clear to me, the teachings spring to mind, complacency no longer occupies my mind, I find enjoyment in the spiritual life, and I have no doubts about the teachings.'"

The Blessed One replied: "Indeed, bhikkhu, this happens when 1) one is guarded in the sense faculties, 2) applies moderation in eating, 3) is dedicated to wakefulness, 4) has insight into wholesome qualities, and 5) engages in the development of the awakening factors during the first and last watch of the night. As a result, the body does not feel as if intoxicated, the directions are clear, the teachings spring to mind, complacency does not occupy the mind, one finds enjoyment in the spiritual life, and there are no doubts about the teachings.

Therefore, bhikkhus, you should train yourselves thus: 'We will be guarded in the sense faculties, apply moderation in eating, be dedicated to wakefulness, develop insight into wholesome qualities, and engage in the development of the awakening factors during the first and last watch of the night.' This is how you should train yourselves."

------

If one has doubts about the teachings of the Buddha, one can harness it by developing an inquisitive mind to learn, reflect and to practice in accordance to the gradual training guidelines over a period of a few months to several months, reflecting on:

-

The growth in the qualities of the mind such as diligence, contentment, persistence, clarity of thinking, and

-

Improvements in one's personal and professional relationships

Related Teachings:

Gradual Training, Gradual Practice, and Gradual Progress (MN 107) - The gradual training guideline teaching of the Buddha is how a student starting out in the teachings of the Buddha should gradually practice in to see gradual progress.

Gradual training and gradual progress: The Habit Curve - The gradual training guidelines linked to the science of forming new habits. Each training area when practiced in as a new habit to cultivate until it becomes easy, automatic and second nature, leads to gradual progress on the path to enlightenment.

-

-

I Will Not Tell An Intentional Lie Even As A Joke (From MN 61)

> The Buddha teaches Rāhula about the importance of truthfulness, teaching him to not tell an intentional lie even as a joke.

Thus have I heard - At one time, the Blessed One was dwelling in Rājagaha, in the Bamboo Grove, the Squirrel Sanctuary.

Now at that time, the venerable Rāhula was dwelling at Ambalaṭṭhika. Then the Blessed One, having arisen from seclusion in the evening time, approached Ambalaṭṭhika, where the venerable Rāhula was. The venerable Rāhula saw the Blessed One approaching from afar. Having seen him, he prepared a seat and water for his feet. The Blessed One sat down on the prepared seat. Having sat down, he washed his feet. The venerable Rāhula also, having paid homage to the Blessed One, sat down to one side.

An Intentional Lie

Then the Blessed One placed a small amount of leftover water in the water vessel and addressed the venerable Rāhula: "Rāhula, do you see this small amount of leftover water in the water vessel?"

"Yes, venerable sir."

"Even so little, Rāhula, is the asceticism of those who do not feel shame in telling an intentional lie."

Then the Blessed One, having discarded the small amount of leftover water, addressed the venerable Rāhula: "Do you see this small amount of leftover water discarded, Rāhula?"

"Yes, venerable sir."

"Thus, discarded, Rāhula, is the asceticism of those who do not feel shame in telling an intentional lie."

Then the Blessed One, having overturned that water vessel, addressed the venerable Rāhula: "Do you see this overturned water vessel, Rāhula?"

"Yes, venerable sir."

"Thus overturned, Rāhula, is the asceticism of those who do not feel shame in telling an intentional lie."

Then the Blessed One, having turned the water vessel upright, addressed the venerable Rāhula: "Rāhula, do you see this hollow and empty water vessel?"

"Yes, venerable sir."

"Even so hollow and empty, Rāhula, is the asceticism of those who do not feel shame in telling an intentional lie."

Simile Of The King's Elephant

"Just as, Rāhula, a king's elephant with sharp tusks, of a mighty stature, well bred, accustomed to the battlefield, engaged in battle, acts with his front feet, acts with his hind feet, acts with his front body, acts with his hind body, acts with his head, acts with his ears, acts with his tusks, acts with his tail; however, he protects his trunk. Then his rider would think: 'This king's elephant with sharp tusks, mighty stature, well bred, accustomed to the battlefield, engaged in battle, acts with his front feet, acts with his hind feet, and acts with his tail; however, it protects his trunk. He has not yet given up his life.'

When, Rāhula, a king's elephant with sharp tusks, mighty stature, well bred, accustomed to the battlefield, engaged in battle, acts with his front feet, acts with his hind feet, acts with his front body, acts with his hind body, acts with his head, acts with his ears, acts with his tusks, acts with his tail, and acts with his trunk, then his rider would think: 'This king's elephant with sharp tusks, mighty stature, well bred, accustomed to the battlefield, engaged in battle, acts with his front feet, acts with his hind feet, acts with his front body, acts with his hind body, acts with his head, acts with his ears, acts with his tusks, acts with his tail, and acts with his trunk. He has given up his life. Now there is nothing that the king's elephant will not do.'

Just so, Rāhula, for anyone who does not feel shame in telling an intentional lie, there is no evil that they will not do, I say. Therefore, Rāhula, you should train yourself thus: 'I will not tell an intentional lie even as a joke.' This is how you should train yourself, Rāhula.

-------

Related Teachings:

Five factors of well-spoken speech (AN 5.198) - Speech endowed with these five factors is well-spoken, not ill-spoken, blameless, and irreproachable to the wise.

A line drawn in water | A teaching on speech (AN 3.132) - The Buddha is sharing a guidance here on how to harmoniously interact with others, even in the face of hostility. This is a quality one will gradually cultivate as they work towards enlightenment.

Who to not associate with (AN 3.27) - The Buddha shares guideline on choosing one's associations and company. For it is through associations that one can decline, avoid decline or grow in qualities.

-

Contempt (ITI 5)

Thus it was said by the Blessed One, said by the Arahant, I have heard:

"Bhikkhus, abandon one thing; I am your guarantor for non-returning. What one thing? Bhikkhus, abandon contempt (ungratefulness); I am your guarantor for non-returning."

The Blessed One spoke this matter. Therefore, it is said thus:

> "When overcome by contempt or ungratefulness, beings go to a bad destination; Completely comprehending contempt and ungratefulness, those with insight abandon it; Having abandoned it, they do not come again, to this world at any time."

This matter too was spoken by the Blessed One, thus have I heard.

------

Picture: The Princess and the Pea, Edmund Dulac, 1911

Related Teachings:

Five ways to remove arisen resentment (AN 5.161) - 1) loving-kindness, 2) compassion, 3) equanimity, 4) disregarding and non-attention, 5) reflection on kamma.

Only by letting go of resentment is hatred stilled (DhP 3, 4, 5) - Hatred is never reconciled by hatred in this world. Only by non-hatred is hatred reconciled.

The Mind of Loving-Kindness (MN 21) - A discourse full of vibrant and memorable similes, on the importance of patience and love even when faced with abuse and criticism. The Buddha finishes with the simile of the saw, one of the most memorable similes found in the discourses.

-

Little Learning (AN 4.6)

"There are these four kinds of persons found existing in the world. Which four?

> One with little learning who is not accomplished by that learning,

> One with little learning who is accomplished by that learning,

> One with much learning who is not accomplished by that learning,

> One with much learning who is accomplished by that learning.

And how, bhikkhus, is a person with little learning not accomplished by that learning? Here, bhikkhus, some person has little learning — of discourses, mixed prose and verse, expositions, verses, inspired utterances, sayings, birth stories, marvelous accounts, and analytical texts. He, not understanding the meaning of that little learning, not understanding the dhamma, does not practice according to the dhamma. Thus, bhikkhus, a person with little learning is not accomplished by that learning.

And how, bhikkhus, is a person with little learning accomplished by that learning? Here, bhikkhus, some person has little learning — of discourses, mixed prose and verse, expositions, verses, inspired utterances, sayings, birth stories, marvelous accounts, and analytical texts. He, understanding the meaning of that little learning, understanding the dhamma, practices according to the dhamma. Thus, bhikkhus, a person with little learning is accomplished by that learning.

And how, bhikkhus, is a person with much learning not accomplished by that learning? Here, bhikkhus, some person has much learning — of discourses, mixed prose and verse, expositions, verses, inspired utterances, sayings, birth stories, marvelous accounts, and analytical texts. He, not understanding the meaning of that much learning, not understanding the dhamma, does not practice according to the dhamma. Thus, bhikkhus, a person with much learning is not accomplished by that learning.

And how, bhikkhus, is a person with much learning accomplished by that learning? Here, bhikkhus, some person has much learning — of discourses, mixed prose and verse, expositions, verses, inspired utterances, sayings, birth stories, marvelous accounts, and analytical texts. He, understanding the meaning of that much learning, understanding the dhamma, practices according to the dhamma. Thus, bhikkhus, a person with much learning is accomplished by that learning.

These, bhikkhus, are the four types of persons existing in the world.

> If one has little learning

> and is not composed in moral conduct,

> He is criticized for both —

> his virtue and his learning.

> If one has little learning

> but is well-composed in moral conduct,

> He is praised for his virtue,

> and his learning flourishes.

> If one has much learning

> but is not composed in moral conduct,

> He is criticized for his virtue,

> and his learning does not flourish.

> If one has much learning

> and is well-composed in moral conduct,

> He is praised for both —

> his virtue and his learning.

> A well-learned one who knows the dhamma by heart,

> A wise disciple of the Buddha,

> Like a golden ornament,

> who could criticize him?

> The deities praise him,

> and he is praised even by Brahmā (God)."

------

Related Teachings:

Eight states to observe for to verify if one has understood the true dhamma (AN 8.53) - A teaching by the Buddha on investing and independently verifying true dhamma from counterfeit dhamma.

Be an island unto yourself, with no other refuge (SN 47.13) - On the passing away of Sāriputta, the Buddha advises Ānanda to be an island unto himself, with no other refuge, with the Dhamma as his island, with the Dhamma as his refuge, not dependent on another as a refuge.

-

Cultivation of the four jhānas (SN 53.1-12)

> Cultivation of the four jhānas slants, slopes, and inclines one towards Nibbāna

At Sāvatthi.

There the Blessed One said:

"Bhikkhus, there are these four jhānas. What four?

Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu, quite secluded from sensual pleasures and unwholesome mental states, with reflection and examination (of thoughts), born of seclusion, filled with joyful pleasure, enters and dwells in the first jhāna.

With the subsiding of reflection and examination (of thoughts), experiencing internal tranquility and unification of mind, devoid of reflection and examination, born of collectedness and filled with joyful pleasure, he enters and dwells in the second jhāna.

With the fading away of joyful pleasure, he dwells equanimous and mindful, fully aware, and experiences physical pleasure, which the Noble Ones describe as 'one who dwells happily, equanimous and mindful.' Thus, he enters and dwells in the third jhāna.

With the abandoning of ease (bliss) and suffering (discontentment, stress), and with the previous disappearance of joy and sorrow, experiencing neither painful nor pleasant sensation, and with the purity of equanimity and mindfulness, he enters and dwells in the fourth jhāna.

These, bhikkhus, are the four jhānas.

Just as the river Ganges slants, slopes, and inclines towards the east, so too, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu who develops and cultivates the four jhānas slants, slopes, and inclines towards Nibbāna.

And how, bhikkhus, does a bhikkhu who develops and cultivates the four jhānas slant, slope, and incline towards Nibbāna?

Here, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu, quite secluded from sensual pleasures and unwholesome mental states, with reflection and examination (of thoughts), born of seclusion, filled with joyful pleasure, enters and dwells in the first jhāna.

With the subsiding of reflection and examination (of thoughts), experiencing internal tranquility and unification of mind, devoid of reflection and examination, born of collectedness and filled with joyful pleasure, he enters and dwells in the second jhāna.

With the fading away of joyful pleasure, he dwells equanimous and mindful, fully aware, and experiences physical pleasure, which the Noble Ones describe as 'one who dwells happily, equanimous and mindful.' Thus, he enters and dwells in the third jhāna.

With the abandoning of ease (bliss) and suffering (discontentment, stress), and with the previous disappearance of joy and sorrow, experiencing neither painful nor pleasant sensation, and with the purity of equanimity and mindfulness, he enters and dwells in the fourth jhāna.

Thus, bhikkhus, a bhikkhu who develops and cultivates the four jhānas slants, slopes, and inclines towards Nibbāna."

------

As the stones in this picture throttle the natural flow of the stream of water, likewise, the mental hindrances when present, throttle the flow of the clear experience of the unconditioned enlighten-mental quality of joy. Having cleared the mental hindrances through a well established life practice, one is then naturally able to dwell in the jhānas. One who develops and cultivates the jhānas, slants, slopes and inclines towards Nibbāna.

Related Teachings:

The five hindrances weaken wisdom | simile of side-channels weakening a river's flow (AN 5.51) - The five hindrances weaken wisdom like side-channels weaken a river’s flow.

Thoughts arise from a cause, not without a cause (SN 14.12) - In this teaching, the Buddha is sharing that as one grows in mindfulness, one is able to have a greater choice in recognizing which thoughts are arising and if they're in the unwholesome category, then one is able to apply right effort and abandon them. If they're in the wholesome category, then one is able to apply right effort to sustain and cultivate them.

Six Qualities to Abandon To Dwell in the first jhāna (AN 6.73)

-

Sensual Pleasures Lead to Arrogance And Even Negligence (SN 3.6)

> There are few in the world, who having obtained great wealth, neither become arrogant nor negligent, do not become obsessed with sensual pleasures, and do not act wrongly towards others.

At Sāvatthi.

Once, while sitting to one side, King Pasenadi of Kosala said to the Blessed One: "Here, venerable sir, when I was alone in seclusion, a reflection arose in my mind: 'There are few beings in the world who, having obtained great wealth, neither become arrogant nor negligent, do not become obsessed with sensual pleasures, and do not act wrongly towards others. But there are far more beings in the world who, having obtained great wealth, become arrogant and even negligent, obsessed with sensual pleasures, and act wrongly towards others.'"

"That is how it is, great king, that is how it is, great king. There are indeed few beings in the world who, having obtained great wealth, neither become arrogant nor negligent, do not become obsessed with sensual pleasures, and do not act wrongly towards others. But there are far more beings in the world who, having obtained great wealth, become arrogant and even negligent, obsessed with sensual pleasures, and act wrongly towards others."

The Blessed One said this. Having spoken this, the Well-Gone One further said this:

> "Enamoured by sensual pleasures, Greedy, infatuated with desires; They do not realize they have gone too far, Like deer that enters the trap laid out; Afterwards, it becomes painful for them, For the result of their actions is bad."

------

Related Teachings:

The Fever of Sensual Pleasures (from MN 75) - Accused by a hedonist of being too negative, the Buddha recounts the luxury of his upbringing, and his realization of how little value there was in such things. Through renunciation he found a far greater pleasure.

Sensuality is subject to time, of much stress (SN 1.20) - A deity tries to persuade a monk to first enjoy sensual pleasures and then go forth.

Held by Two Kinds of Misconceptions (ITI 49) - How those with vision differ from those who adhere to craving for rebirth and those who slip past into craving to be annihilated.

-

Engaging in Debate (SnP 4.8)

In this verse, the Buddha advises Pasūra on the futility of engaging in debates and the dangers of becoming conceited.

> "Here alone is purity," they say, Denying that there is purification in other teachings; Based on what they rely on, they speak of purity, Being established in diverse individual truths.

> They who desire debate, entering an assembly, Burning fools among each other; Clinging to views dependent on others, they argue with words, Desiring praise, they are skilled in arguing.

> Engaged in debate in the midst of an assembly, Desiring praise, there arises anxiety; However, in defeat, they become despondent, Upset by criticism, they seek faults in others.

> When their argument is declared lacking, Refuted by the questioners in the assembly; One whose view is refuted laments, Thinking they have been surpassed, they feel inferior.

> These debates arise among ascetics, In these, there is both elation and dejection; Also seeing this, one should refrain from debates, For there is no purpose in obtaining praise or in gaining approval.

> One might be praised, however, there, Having declared an argument in the midst of the assembly; He laughs and becomes conceited on account of that, Having achieved what his mind desired.

> That exaltation becomes the ground for his downfall, Filled with pride, he speaks arrogantly; Seeing this too, one should not engage in debate, For the wise do not claim purity through debates.

> Just as a hero, challenged at the king's feast, Goes roaring with a desire to fight; By whatever means, hero, you should withdraw, There was no prior reason for this contest.

> Those who cling to their views and argue, Saying only "this is true" and debate it; You should tell them, "There's no point in that," For with debate arises opposition.

> However, those who have conquered the army of defilements, Acting with views that do not conflict with views; What can you gain among them, Pasūra, For they have nothing taken as supreme.

> Then you, full of thoughts, Reflecting on views in your mind; Having come together with the pure one, You indeed cannot keep up.

------

Related Teachings:

Skillfully grasping the Dhamma: The Simile of Water Snake (from MN 22) - In this teaching, the Buddha shares on learning the Dhamma by investigating its meaning with close examination, through the simile of skillfully holding a water snake.

Possessions, Respect and Popularity | Fishing Hook (SN 17.2) - Possessions, respect, and popularity are painful, severe, and obstructive to the attainment of the unsurpassed safety from the yoke (freedom from bondage).

-

Lobha sutta | Greed (ITI 1)

Thus it was said by the Blessed One, said by the Arahant, I have heard:

"Bhikkhus, abandon one thing; I am your guarantor for non-returning. What one thing? Bhikkhus, abandon greed; I am your guarantor for non-returning.

The Blessed One spoke this matter. Therefore, it is said thus:

> "When overcome by greed, beings go to a bad destination; Completely comprehending greed, those with insight abandon it; Having abandoned it, they do not come again, to this world at any time."

This matter too was spoken by the Blessed One, thus have I heard.

------

Greed is a defilement (a taint) of the mind that manifests as craving for material possessions, for consuming, for having experiences. To completely comprehend greed, one should understand the attachment, the holding on to, and clinging at the five aggregates.

Related Teachings:

Steadying the mind against the poisons of greed, hate and delusion (AN 4.117) - The Buddha's teachings when practiced become a support for the mind, allowing it to remain steady in situations that once used to shake it up.

Understanding 30 mental qualities that lead to enlightenment ↗️ - Greed, hate and delusion are the last layer of the ten layers of three mental qualities each to be uprooted to get to enlightenment. This teaching can be used to see the next layer of qualities to uproot and its antidote qualities to be cultivated.

A teaching on the Turning of the Aggregates of Clinging (SN 22.56) - The Buddha did not claim to be awakened until he had fully understood each of the five aggregates in the light of each of the four noble truths. This discourse includes definitions of each of the aggregates.

The Continuance of Consciousness (SN 12.38) - Intentions, plans or underlying tendencies become the basis for the continuance of consciousness from one life to the next.

-

A Discourse on Eating, Feelings, and Diligence (MN 70)

This teaching is also part of the section The Planes of Realization from "In the Buddha's Words" by Bhikkhu Bodhi.

> The Buddha starts out by advising the bhikkhus to eat only during the day, without having a meal at night, explaining the interplay of how pleasant, painful and neither-pleasant-nor-painful feelings can lead to furthering of unwholesome or wholesome states. He then shares on the seven kinds of persons and which kinds must act with diligence. The Buddha concludes by describing how final knowledge is attained gradually.

Thus have I heard - One time, the Blessed One was wandering in the Kāsī region along with a large group of bhikkhus. There, the Blessed One addressed the bhikkhus:

Not Eating At Night

"Bhikkhus, I eat only during the day, without having a meal at night. By not eating at night, I experience fewer ailments and illnesses, nimbleness, strength, and ease of living. Therefore, bhikkhus, you too should eat only during the day, without having a meal at night. By not eating at night, you will experience fewer ailments and illnesses, nimbleness, strength, and ease of living."

"Yes, venerable sir," the bhikkhus replied to the Blessed One.

Then, while wandering in stages through the Kāsī region, the Blessed One arrived at a Kāsī town of Kīṭāgiri. There, the Blessed One stayed in this Kāsī town, Kīṭāgiri.

At that time, a group of bhikkhus led by Assaji and Punabbasuka were residing at Kīṭāgiri. Then, several bhikkhus went to visit these bhikkhus and said to them: "Friends, the Blessed One eats only during the day, without having a meal at night, and the bhikkhu saṅgha does the same. By not eating at night, they experience fewer ailments and illnesses, nimbleness, strength, and ease of living. Therefore, friends, you too should eat only during the day, without having a meal at night. By doing so, you will experience fewer ailments and illnesses, nimbleness, strength, and ease of living."

When this was said, the bhikkhus led by Assaji and Punabbasuka said to those bhikkhus: "Friends, we eat in the evening, in the morning, and during the day outside of the proper time. By eating in the evening, morning, and during the day outside of the proper time, we experience fewer ailments and illnesses, nimbleness, strength, and ease of living. Why should we abandon what is evident and pursue what is uncertain? We will continue to eat in the evening, morning, and during the day outside of the proper time."

When the bhikkhus were unable to convince the bhikkhus led by Assaji and Punabbasuka, they went to the Blessed One; having approached, they paid homage to the Blessed One and sat down to one side. Sitting to one side, those bhikkhus said to the Blessed One: "Venerable sir, we went to the bhikkhus led by Assaji and Punabbasuka; having approached, we said to them: 'Friends, the Blessed One only eats during the day, without having a meal at night, and the bhikkhu saṅgha does the same; by not eating at night, they experience fewer ailments and illnesses, nimbleness, strength, and ease of living. Therefore, friends, you too should abstain from eating at night. By so doing, you too will experience fewer ailments and illnesses, nimbleness, strength, and ease of living.' When this was said, venerable sir, the bhikkhus led by Assaji and Punabbasuka said to us: 'Friends, we eat in the evening, in the morning, and during the day outside of the proper time. By eating in the evening, morning, and during the day, we experience fewer ailments and illnesses, nimbleness, strength, and ease of living. Why should we abandon what is evident and pursue what is uncertain? We will continue to eat in the evening, morning, and during the day.' Since we could not convince the bhikkhus led by Assaji and Punabbasuka, venerable sir, we have come to inform the Blessed One of this matter."

Then the Blessed One addressed a certain bhikkhu: "Come, bhikkhu, in my name, call the bhikkhus led by Assaji and Punabbasuka, saying: 'The teacher calls you, venerables.'"

"Yes, venerable sir," the bhikkhu replied. Then that bhikkhu, having answered the Blessed One, approached the bhikkhus led by Assaji and Punabbasuka; having approached them, he said, "The teacher calls you, venerables."

"Yes, friend," the bhikkhus led by Assaji and Punabbasuka replied to that bhikkhu, and they approached the Blessed One; having approached and paid homage to the Blessed One, they sat down to one side. After they sat to one side, the Blessed One said this:

"Is it true, bhikkhus, that several bhikkhus approached you and said: 'The Blessed One and the community of bhikkhus eat only during the day, without having a meal at night; by not eating at night, they experience fewer ailments, fewer illnesses, nimbleness, strength, and ease of living. Come, friends, you too should eat only during the day, without having a meal at night. By not eating at night, you too will experience fewer ailments, fewer illnesses, nimbleness, strength, and ease of living.' And when this was said, bhikkhus, did you respond to those bhikkhus: 'Friends, we eat in the evening, in the morning, and during the day outside of the proper time. By eating in the evening, morning, and during the day outside of the proper time, we experience fewer ailments, fewer illnesses, nimbleness, strength, and ease of living. Why should we abandon what is evident and pursue what is uncertain? We will continue to eat in the evening, morning, and during the day outside of the proper time.'"

"Yes, venerable sir."

Feelings and Unwholesome and Wholesome States

"Bhikkhus, do you understand me to teach the Dhamma in such a way as this: 'Whatever this person experiences, whether pleasant or painful or neither-painful-nor-pleasant, unwholesome states diminish in him and wholesome states increase'?"

"No, venerable sir."

"Surely, bhikkhus, do you understand the Dhamma as I have taught it: that in the case of some person, experiencing a pleasant feeling, unwholesome states increase and wholesome states diminish; but in the case of another person, experiencing a pleasant feeling, unwholesome states diminish and wholesome states increase. In the case of some person, experiencing a painful feeling, unwholesome states increase and wholesome states diminish; but in the case of another person, experiencing a painful feeling, unwholesome states diminish and wholesome states increase. In the case of some person, experiencing a neither-painful-nor-pleasant feeling, unwholesome states increase and wholesome states diminish; but in the case of another person, experiencing a neither-painful-nor-pleasant feeling, unwholesome states diminish and wholesome states increase?"

"Yes, venerable sir."

Pleasant Feelings

"Good, bhikkhus. And if it were unknown to me, unseen, not understood, not realized, or not contacted through wisdom thus: 'Here, for some person, experiencing such a pleasant feeling, unwholesome states increase and wholesome states diminish,' would it be appropriate for me, not knowing that, to say: 'Abandon such a pleasant feeling'?"

"No, venerable sir."

"Bhikkhus, because this has been known, seen, understood, realized, and contacted by me through wisdom: 'Here, for some person, experiencing such a pleasant feeling, unwholesome states increase and wholesome states diminish,' therefore I say, 'Abandon such a pleasant feeling.' If it had been unknown to me, unseen, not understood, not realized, or not contacted through wisdom: 'Here, for some person, experiencing such a pleasant feeling, unwholesome states diminish and wholesome states increase,' would it be appropriate for me, not knowing that, to say, 'Dwell experiencing such a pleasant feeling'?"

"No, venerable sir."

"Bhikkhus, because this has been known, seen, understood, realized, and contacted by me through wisdom: 'Here, for some person, experiencing such a pleasant feeling, unwholesome states diminish and wholesome states increase,' therefore I say, 'Dwell experiencing such a pleasant feeling.'

Painful Feelings

If it had been unknown to me, unseen, not understood, not realized, or not contacted through wisdom: 'Here, for some person, experiencing such a painful feeling, unwholesome states increase and wholesome states diminish,' would it be appropriate for me, not knowing that, to say, 'Abandon such a painful feeling'?""

"No, venerable sir."

"Bhikkhus, because this has been known, seen, understood, realized, and contacted by me through wisdom: 'Here, for some person, experiencing such a painful feeling, unwholesome states increase and wholesome states diminish,' therefore I say, 'Abandon such a painful feeling.' If it had been unknown to me, unseen, not understood, not realized, or not contacted through wisdom: 'Here, for some person, experiencing such a painful feeling, unwholesome states diminish and wholesome states increase,' would it be appropriate for me, not knowing that, to say, 'Dwell experiencing such a painful feeling'?"

"No, venerable sir."

"Bhikkhus, because this has been known, seen, understood, realized, and contacted by me through wisdom: 'Here, for some person, experiencing such a painful feeling, unwholesome states diminish and wholesome states increase,' therefore I say, 'Dwell experiencing such a painful feeling.'

Neither-Painful-Nor-Pleasant Feelings

If it had been unknown to me, unseen, not understood, not realized, or not contacted through wisdom: 'Here, for some person, experiencing such a neither-painful-nor-pleasant feeling, unwholesome states increase and wholesome states diminish,' would it be appropriate for me, not knowing that, to say, 'Abandon such a neither-painful-nor-pleasant feeling'?”

"No, venerable sir."

"Bhikkhus, because this has been known, seen, understood, realized, and contacted by me through wisdom: 'Here, for some person, experiencing such a neither-painful-nor-pleasant feeling, unwholesome states increase and wholesome states diminish,' therefore I say, 'Abandon such a neither-painful-nor-pleasant feeling.' If it had been unknown to me, unseen, not understood, not realized, or not contacted through wisdom: 'Here, for some person, experiencing such a neither-painful-nor-pleasant feeling, unwholesome states diminish and wholesome states increase,' would it be appropriate for me, not knowing that, to say, 'Dwell experiencing such a neither-painful-nor-pleasant feeling'?"

"No, venerable sir."